Calligraphy and Sutra Writing - 佛经与书法

...

index | publikációk | facebook oldalunk

Zhang Jizhi (張即之, 1186–1266) transcribed the Diamond Sutra 《金剛般若波羅蜜經》 (CBETA T08n0235) in 1248 for his deceased wife. These lines were appended in a colophon by a Confucianist layman. Zhang Jizhi was a devout Buddhist with close ties to disciples of the influential Chan master Wuzhun Shifan (無準師範, 1177– 1249). A scholar-official, Zhang was well versed in calligraphy and hailed as the last great calligrapher of the Southern Song (1127–1279).

This Diamond Sutra 《金剛般若波羅蜜經》 was written for religious reasons and the manuscript treated accordingly. It was stored in the sutra repository at Huideng Monastery (慧燈寺) in Suzhou and was only retrieved on important religious occasions. Now it is part of a collection kept by the Palace Museum in Beijing and has been catalogued as a work of calligraphy.

[…] I sigh that this sutra the Buddhists treasure is also treasured by Confucianists as calligraphy by a sage worthy. Certainly it should be treasured. Jizhi was famous in the Song Dynasty for his calligraphy, and we Confucianists treasure his ink traces. […]

From a colophon by Xie Ju (謝矩) in 1402, following a transcription of the Diamond Sutra by the Song dynasty calligrapher Zhang Jizhi made in 1248; album, now in Beijing’s Palace Museum, nine colophons.

Transcribing a sutra is a religious exercise; the content of the text that is chosen matters because of its ritual efficacy. On the other hand, presenting a sutra as a gift adds a new dimension to it that goes beyond this purely religious aspect. The text is fix, for eternity; not a single character may be altered. No personal message or hidden meaning seems to lie below the surface of the words. An "innocent" text – unlike a poem, for example, – always connected to its author and their fate. Yet the calligrapher could and did invest a sutra transcription with a personal, social, historical and even political subtext by consciously selecting a specific, meaningful calligraphic style. The recipient of such a work and later owners demonstrated their "reading" by acknowledging this in colophons appended to the sutra. The majority of colophons discuss such sutra transcriptions in calligraphic terms, ignoring the religious contents of the text.

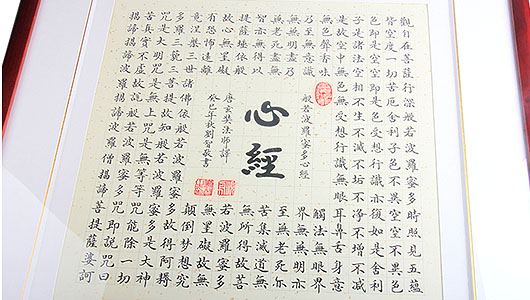

A painting by Qiu Ying (仇英, ~1494 ~1552), Zhao Mengfu Writing the Heart Sutra in Exchange for Tea (see picture below), illustrates how a sutra transcription gained new life as a work of art when it entered the literati sphere where it was appreciated according to a different set of values. The picture shows the famous painter, calligrapher and statesman Zhao Mengfu (趙孟頫, 1254–1322) in a garden setting.

Qiu Ying (c. 1494-c. 1552), Zhao Mengfu Writing the "Heart" Sutra in Exchange for Tea (寫經換茶圖), hand scroll, ink and light colour on paper, 21.1 × 77.2 cm, detail

Across from him, seated at a stone table, is a Buddhist monk. A piece of paper is spread out on the table and Zhao is holding a brush in his hand, ready to write. An attendant approaches with a container of tea, a second servant boy is boiling some water and a third comes onto the scene with a bundle of scrolls in his arms. Beyond the fence, two birds are pecking grain from a lotus pedestal, a hint at a Buddhist ritual for hungry ghosts. The painting was commissioned by one of Qiu Ying’s patrons, the art collector and lay Buddhist Zhou Fenglai (周鳯來, 1523–1555). Zhou himself practised calligraphy in the style of Zhao Mengfu. The painting was meant as a companion piece for a poem in Zhou’s collection. The poem was a piece of calligraphy by Zhao Mengfu in which he writes about copying the Heart Sutra for a certain priest (Gong) in exchange for tea.

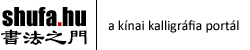

Heart Sutra calligraphy (心经)

The sutra copy mentioned in the poem was no longer extant in the sixteenth century. Thus, Zhou Fenglai asked the famous calligrapher, painter and fellow art connoisseur Wen Zhengming (文徵明, 1470– 1559) to create a replacement for it. Zhou resided in Kunshan near Suzhou, where Wen Zhengming was the most highly esteemed artist. Their collaboration on this project is a clear indication that they were both part of a closely woven local network, participants in literati cultural activities. Once Wen Zhengming had completed the transcription of the sutra in 1542, it was mounted together with Qiu Ying’s painting and Zhao Mengfu’s poem from Zhou Fenglai’s collection.

In 1543, two of Wen Zhengming’s sons, Wen Peng (文彭, 1498–1573) and Wen Jia (文嘉, 1501–1583), both artists in their own right, supplied a colophon each.6 The texts these contained discuss the sutra copy and the poem exclusively in calligraphic terms. They place Zhao Mengfu’s achievements in the art of calligraphy firmly in line with Wang Xizhi (王羲 之, 303–361) and Su Shi (Dongpo style - 蘇軾, 1037–1101). Wen Peng equates sutra writing in return for tea with two other well-known transactions, involving calligraphy:

[…] I-shao [Wang Xizhi] wrote in exchange for a flock of geese. Su Tung-po (Su Shi) wrote in exchange for meat […]

In 1584, a later owner of this scroll – the art connoisseur Wang Shimao (王世懋, 1536–158) who had obtained possession of the scroll from Zhou Fenglai’s family – cut off Zhao Mengfu’s poem. Wang re-mounted the poem along with a transcription of the Heart Sutra – also by Zhao Mengfu – taken from his own collection. As he explained in a colophon relating to Qiu Ying’s painting:

[…] I was able to get two complete works of art in one clever stroke […]

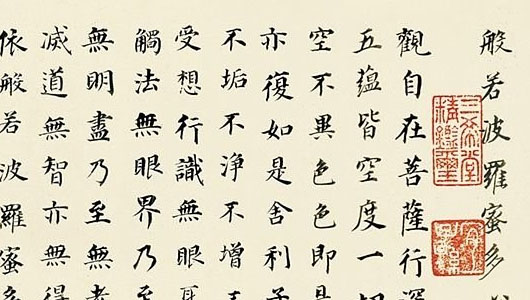

From the same colophon we learn that this Heart Sutra had been transcribed in xingshu (semi-cursive script), a type of script for which Zhao Mengfu was particularly well known, and not in kaishu (regular or standard script), which was commonly employed to copy sutras. It had been a regular routine for Zhao Mengfu to transcribe sutras, to which he often added paintings of Buddhist deities like the Bodhisattva Guanyin – usually one before and one after the text. This was more than a purely religious exercise; it was definitely also an exercise in calligraphy (perhaps even more so). Unlike poems, colophons or letters, such sutra copies were free of loaded connotations and accumulated history. The copier’s personal and individual expression was concealed in the style and form of the handwriting he used. Such works of art lent themselves particularly well to meeting one’s social obligations, i.e. as gifts, the possession of which would not endanger the recipient if the political wind happened to shift. Zhao Mengfu had been a scion of the Song Imperial family. His decision to follow the call to serve at the Court of the foreign Mongol rulers as a high-ranking official did not pass uncriticised. When he was asked for a piece of calligraphy by the Emperor, Zhao, his wife Guan Daosheng (管道昇, 1262– 1319) and their son Zhao Yong (趙雍, 1289 ~1360) chose to present him with a sutra transcription on several occasions, thus avoiding any implications or taking an overt stance on the morally difficult issue of loyalty. As a calligrapher, Zhao Mengfu strictly adhered to the orthodox Wang Xizhi school.

It was the Tang dynasty (618–907) emperor Taizong (太宗, 629–649) who had made Wang Xizhi’s calligraphy an authoritative standard. This was a political act only partly motivated by aesthetic considerations. Officials employed the calligraphic style of Wang Xizhi and his son Wang Xianzhi (王獻之, 344–386) throughout the Empire. This fostered a strong sense of belonging to the ruling elite, of shared value, and of allegiance to the central power In the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), when factional struggles within the political elite were rampant, this close connection between orthodox calligraphic style and Confucian values was well understood. Thus, when Wang Shimao created a second scroll with a sutra from his collection transcribed by Zhao Mengfu and appended a colophon to Qiu Ying’s painting, discussing the artwork in aesthetic and calligraphic terms, he positioned himself in an ongoing discourse, not on art but on politics!

Dong Qichang (董其昌), Heart Sutra (1627), album of six leaves, each 21.5 × 25 cm, ink on paper, detail.

Zhao Mengfu’s calligraphy was in line with the orthodox Wang Xizhi tradition and hence acceptable at Court. His political position, on the other hand, was a controversial matter during the Ming period. In the eyes of many critics, Zhao had violated Confucian ethics by serving as an official under a foreign regime despite his descent from the fallen Song Imperial family. He was therefore considered a traitor. When Wang commented on Zhao’s calligraphy in his colophon, he at the same time conveyed a subtle political message which left a back door open allowing him to either side with Zhao Mengfu’s critics or admirers, depending on how the political wind shifted at Court. Such clever, manoeuvring, ambiguous writing was necessary to avoid any fatal consequences should the opposing faction win the upper hand. Wang Shimao had passed the imperial examinations in 1559 and subsequently served as an official in Nanjing. He entertained excellent ties with the literati from the urban centres of South-east China (Jiangnan), a fact attested to by his obtaining the Qiu Ying scroll from Zhou Fenglai’s family and, together with his brother Wang Shizhen (王世貞, 1526– 1590), building one of the best collections of painting and calligraphy in the entire Empire.

What Dong Qichang used as models of calligraphy by those two eminent Tang calligraphers were not sutra copies but other works written in kaishu that he had in his art collection. Which specific works of calligraphy by Ouyang and Yan he had actually seen, handled, copied and commented on is documented quite well. Apart from calligraphies in his own art collection, Dong Qichang also had access to firstrate works in the collections of such eminent connoisseurs as Xiang Yuanbian (項元汴, 1525–1590). Whether or not Ouyang Xun or Yan Zhenqing ever transcribed any sutras is a controversial matter. Yet it had been common practice to describe the calligraphic style of a sutra as Outi (歐體, in the style of Ouyang Xun) or Yanti (顏體, in the style of Yan Zhenqins) since at least the Ming dynasty. The Suti (蘇 體, in the style of Su Shi) was less prominent.

There are rubbings of a Heart Sutra 《般若波羅蜜多心經》 (CBETA T08n0251) by Ouyang Xun (see the picture) containing his signature and a date from the year 635. The text is a translation by the pilgrim monk Xuanzang (玄奘, 602–664), who translated this sutra in 649. This post-dates Ouyang’s Heart Sutra by fourteen years. In other words, it is impossible that Ouyang Xun used Xuanzang’s Chinese translation of this sutra. These facts point to an interesting phenomenon in calligraphy, to a practice still commonly resorted to in China nowadays, namely that of selecting individual characters from various works of calligraphy and re-assembling them to form a new piece of writing. One well-known example is the Thousand-Character Essay (Qianzi Wen 千字文) [pdf version is available here], which consists of a thousand words or characters that only occur once in the entire text. Legend has it that Emperor Wu of the Liang dynasty (502–549) selected a thousand characters from various works of calligraphy by Wang Xizhi and asked the scholar Zhou Xingsi (周興嗣, 470–521) to make a meaningful text out of them. The Thousand-Character Essay, which was written in Wang Xizhi’s distinct style, was intended to serve the crown prince as a model for practising calligraphy. There are handwritten and printed sutras penned in the calligraphic style of Ouyang Xun and Yan Zhenqing from at least the Song dynasty (960–1279) onwards, although no evidence actually exists that either of these men ever copied a sutra. Sutras created in retrospect in the style of famous calligraphers lent these copies enormous prestige, not because of the contents of the text, but because of the weight and importance of the calligraphic style. Printed editions of these sutras were a political tool. The Imperial Court had complete editions of the Buddhist Canon printed and distributed among the major monasteries. The strategy behind this act was to assure the loyalty and allegiance of these monasteries and the Buddhist community to the Imperial Court. Equally anonymous but important and prominent sutra writing, like the monumental Diamond Sutra engraved into the rock at "Sutra Valley" on Mount Tai around the year 570 were associated with the names of famous calligraphers by later epigraphers. On the grounds of stylistic similarities, it is said that Yan Zhenqing’s calligraphy was influenced by the style of this Diamond Sutra. As Amy McNair has convincingly argued, there is no proof of such influence, though […] we have absolutely no evidence that Yan ever visited Sutra Valley or saw ink rubbings taken from inscriptions. The connection cannot be substantiated through documentary evidence, nor is the visual evidence compelling. The critical practice of locating stylistic sources for the writing of wellknown calligraphers in certain exceptional anonymous engraved stele inscriptions of the Northern Dynasties period (386–581) arose during the resurgence of epigraphic study that began during the reign of the Qianlong emperor (1735–1796). Chinese scholars are still wedded to this questionable practice today, as are some Western historians of calligraphy.

This ‘questionable practice’ certainly reached its peak during the Qianlong reign, but had actually been in place since at least the Song dynasty. A prominent example of this practice in the case of the early Qing dynasty was the courtier and art collector Gao Shiqi (高士奇, 1645–1704). He did not manage to pass the imperial examination and consequently had to struggle hard to win the respect of the Emperor and his fellow officials. Gao Shiqi used his art collection and colophon writing as a means of positioning himself in elite society. He was very knowledgeable about painting and calligraphy and perfectly conversant with literati conventions.

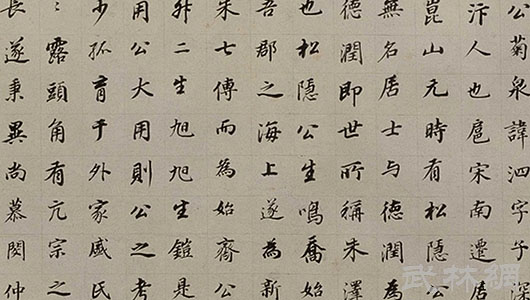

Dong Qichang (董其昌), Diamond Sutra (1625), detail: colophon Gao Shiqi (1645–1704).

In 1693, Gao appended a colophon to a Diamond Sutra written by Dong Qichang in small, regular script in 1625. In his colophon, Gao boldly states that during the Tang dynasty the most important calligraphic style employed when copying sutras was that of Xu Hao (徐浩, 703–782). Specimens of this calligraphy were unobtainable in his time, the early Qing. He continues to prove his connoisseurship by showing his expertise and familiarity with practical aspects of material culture by saying that Dong Qichang had used Song sutra paper in his copy of the Diamond Sutra. Unused Song sutra paper was extremely precious and hard to come by at the time. When a more or less auto didactic, self-made man like Gao Shiqi showed his expertise in matters like identifying a specific type of paper such as Song dynasty sutra paper, it certainly added a feather to his cap. Gao goes on to say in his colophon that in his view, Dong Qichang had based his calligraphic style on that of the Tang master Yan Zhenqing in this particular sutra copy. So by the early Qing, Yan Zhenqing had been elevated – uncritically – as a great copyist of sutras, something for which there is actually no evidence at all. Gao continues to praise Dong’s sutra copy and adds how much he is personally touched and moved by merely looking at the calligraphy. This individual response, formalised as the wording may be, still reveals something of Gao Shiqi’s eager attempt to show to his surrounding fellow courtiers that he took an active part in the transmission and history of this work of calligraphy, very much in the established literati manner. Later, Emperor Qianlong inherited Dong Qichang’s sutra copy with Gao Shiqi’s colophon. Qianlong added several of his seals and had the whole work mounted in an album format, with two Buddhist paintings in gold on indigo paper added after the sutra transcription. The Qianlong Emperor favoured Dong Qichang’s calligraphy so much that he modelled his own handwriting on the master’s calligraphy and had imperially commissioned books printed in Dong Qichang-style regular script.

The earliest known work of calligraphy by Dong Qichang is a copy of the Diamond Sutra dated 1592. He copied the sutra for the souls of his deceased parents, as indicated in his own dedication. Dong then presented the album to Yunqi Temple (雲棲寺) near Hangzhou. The abbot of the monastery at that time was the reformist monk Yunqi Zhuhong (雲棲祩宏, 1535–1615). The sutra copy also bears a dedication by Dong Qichang to Yunqi Zhuhong. The former maintained close contact with the abbot and the temple throughout his life. In 1604, he was asked to write the temple record in his calligraphy to be engraved onto a stele. For Zhuhong’s eightieth birthday in 1614, Dong Qichang gave him a copy of a Pure Land Sutra. In a comment on this sutra transcript, Dong Qichang does not remark on any religious matters or on his friendship with the highly respected older monk, but considers this transcription a work of calligraphy. He compares his Pure Land Sutra to a copy by Zhao Mengfu, which the latter had dedicated to his friend, the Chan abbot Zhongfeng Mingben (中峰明本, 1262–1323). With unusual modesty, Dong says that the calligraphy used in his transcription is not as good a Zhao Mengfu’s. For Dong Qichang, Zhao Mengfu was an arch rival – a calligrapher whom he strove to surpass. By 1614, Dong’s calligraphy had certainly reached a level of maturity and excellency that was on a par with that of the Yuan dynasty giant of calligraphy. With his pretence at modesty, Dong was, in fact, seeking confirmation to the contrary, namely that his calligraphy was actually better than Zhao Mengfu’s. In 1615, Dong Qichang transcribed the Amida Sutra, which he also presented to Yunqi Temple.

When Dong Qichang copied the Diamond Sutra, his calligraphy was still at an early formative stage. Unlike the Heart Sutra, which is short and easy to memorise, the text of the Diamond Sutra is rather long and lends itself well as a calligraphic exercise. This is precisely what Dong Qichang did. He wrote the sections of the sutra in various styles used by famous calligraphers of the past; the change in style is discernable. Sections one to five are written in the style of Zhong Yao (鍾繇, 151–230), sections six to nine in the manner of the Two Wangs (Wang Xizhi and his son Wang Xianzhi), sections ten to thirteen in Ouyang Xun’s hand, sections fourteen to twenty are based on Mi Fu (米芾, 1051–1107) with some elements from Yan Zhenqing, and the final sections (up to thirty-two) again follow Wang Xizhi’s stylistic approach. It is noteworthy that these names read like a Who’s Who of orthodox calligraphic tradition. By copying different sections of this sutra in different styles, Dong Qichang demonstrated his familiarity with works of calligraphy by these earlier masters and at the same time strove to be included in this illustrious lineage as a worthy successor of a centuriesold tradition. From his own comments and other sources, it is known that Dong had had the opportunity to see and occasionally copy or borrow famous works of calligraphy from two of the foremost private art collectors of the time, Xiang Yuanbian and Han Shineng (韓世能, 1528–1598). The list of works Dong was able to study and copy prior to making his transcription of the Diamond Sutra is truly impressive, including Chu Suiliang’s (褚遂良, 597–658) copy of Wang Xizhi’s Orchid Pavilion Preface with a colophon by Mi Fu.

At this point, what mattered most was calligraphic style, stylistic quotations and the models that were selected. The sutra’s religious function – it was stored in the sutra repository and only taken out and recited in temple rituals on important days – was secondary. When Emperor Qianlong visited the South on his inspection tours, he always stopped at Yunqi Temple and asked to see Dong Qichang’s Diamond Sutra. The Emperor’s preference for Dong’s calligraphy was well known. He liked the calligraphy of this sutra transcription so much that he personally wrote the title slip, the frontispiece, appended six lengthy poetic colophons dated 1751, 1757, 1762, 1765, 1780 and 1784 and imprinted a total of nineteen of his seals on it. Sutra transcriptions produced by anonymous monks in the scriptorium of a monastery tended to – quite literally – lead a cloistered existence in the temple or be sent from one temple to another. Once a sutra copy was associated with the name of a famous calligrapher, it left the religious Buddhist environment and entered the Confucian-dominated literati sphere, the ‘world of the red dust’, where the written characters of sacred words lost their innocence and became part of very worldly matters such as issues of loyalty, status, rivalry or political allegiance. This discourse was not carried out openly in words, but concealed in the style and form of the calligraphy.

Notes

- Dardess, John W. (2002), Blood and History in China: The Donglin Faction and Its Repression, 1620–162, (Honolulu).

- Diamond Sutra, written by Dong Qichang (1991), facsimile edition, National Palace Museum: 明 董其昌書金剛般若波羅蜜經 (Taipei; repr. 1993).

- Fujita Kotatsu (1990), ‘The Textual Origins of the Kuan Wu-liangshou ching: A Canonical Scripture of Pure Land Buddhism’, in Robert E. Buswell, Chinese Buddhist Apocrypha (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press), 149–174.

- Goodfellow, Sally W. (ed.) (1980), Eight Dynasties of Chinese Painting: The Collections of the Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, Kansas City, and The Cleveland Museum of Art, with essays by Wai-kam Ho, Sherman E. Lee, Laurence Sickman, Marc F. Wilson (Cleveland).

- Huang Qijiang 黄啓江 (2005), ‘Lun Zhao Mengfu de xiejing yu qi fojiao yinyuan – cong Qiu Ying de “Zhao Mengfu xiejing huan cha tu juan” shuoqi’ ‘論趙孟頫的寫經與其佛教因緣---從仇英 的《趙孟頫寫經換茶圖卷》說起’, Chinese Culture Quarterly 九州學林 2, 4: 2–63; also online: http://www.cciv.cityu.edu.hk/ publication/jiuzhou/txt/6-1-2.txt (accessed on 13 April 2014).

- Lauer, Uta (2012), ‘The Making of a Master: A Letter by Wang Xizhi (303-361) and Its Role in Shaping the Canonical Calligrapher Sage’, in Burglind Jungmann, Adele Schlombs, and Melanie Trede (eds.), Shifting Paradigms in East Asian Visual Culture: A Festschrift in Honor of Lothar Ledderose (Berlin), 259–270.

- McNair, Amy (1998), The Upright Brush: Yan Zhenqing’s Calligraphy and Song Literati Politics (Honolulu).

- —— (2001), ‘Buddhist Literati and Literati Monks: Social and Religious Elements in the Critical Reception of Zhang Jizhi’s Calligraphy’, in Marsha Weidner (ed.), Cultural Intersections in Later Chinese Buddhism (Honolulu).

- The National Palace Museum (ed.) (1993), Dong Qichang fashu tezhan yanjiu tulu 董其昌法書特展研究圖録 Special Exhibition of Tung Ch’i-ch’ang’s Calligraphy (Taipei).

- Wang Qingzheng 汪慶正 (1992), ‘Ink Rubbings of Tung Ch’ichang’s Calligraphy’ ‘董其昌法書刻帖簡述’, in Ho Wai-kam, and Judith G. Smith, The Century of Tung Ch’i-ch’ang (1555– 1636) (Seattle and London).

- Xu Bangda 徐邦达 (1987), Gu shuhua guoyan yaolu: Jin, Sui, Tang, Wudai, Song shufa.古书画过眼要录: 晋隋唐五代宋书法, (Changsha), 555.

- Xu Yuanting 許媛婷 (2006), ‘Cat. entry no. 28: The Lotus Sutra’ ‘ 妙法蓮華經’, in The National Palace Museum (ed.), Grand View: Special Exhibition of Sung Dynasty Rare Books 大觀宋版圖書特 展 (Taipei), 236–243.

- Yü Chün-fang (1981), The Renewal of Buddhism in China: Chuhung and the Late Ming Synthesis (New York).

- Zheng Yinshu 鄭銀淑 (1984), Xiang Yuanbian zhi shuhua shoucang yu yishu 項元汴之書畫収藏與藝術 (Taipei).

- Zhu Huiliang 朱惠良 (1993), ‘Introduction’, in The National Palace Museum (ed.), Dong Qichang fashu tezhan yanjiu tulu 董其昌 法書特展研究圖録 Special Exhibition of Tung Ch’i-ch’ang’s Calligraphy (Taipei), 6–38.

Learn more about the Chinese Calligraphy’s Art at www.shufa.hu