The Artistic Qualities of Chinese Writing

index | szakfordítások és publikációk

Chinese is one of the few languages in which the script not only is a means of com-munication but also is celebrated as an independent form of visual art. The best of Western calligraphy, for example, the scriptures written on parchment by monks in the Middle Ages and the letters written in golden ink by scribes at Buckingham Palace, exemplify its primary function as a means of documentation and communi-cation. One might ask why Western calligraphy didn’t evolve from the functional to the purely artistic, as Chinese calligraphy did. The answer has a lot to do with the nature of the scripts:

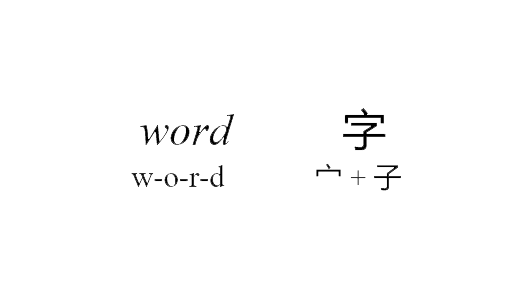

“Word” versus 字 (Chinese character)

Alphabetic writing consists of an inventory of letters that correspond to speech sounds. Sound symbols are simple in structure and small in number, ranging from about twenty to fifty for a particular language. The English alphabet, for example, has twenty-six letters. Each is formed by arranging one to four elements. The letter “o” has only one element; “i” has two, a dot and a vertical line; and the capital letter “E” has four elements. These elements are generally various lines, curves or circles, and dots. In writing, letters are arranged in a linear order to form words and texts. Because of the small number of letters, their frequency of use is high. Furthermore, the same letter repeated in a text is always supposed to be written in exactly the same way, except for larger or more ornate capital letters at the beginning of texts. Consequently, Western calligraphy concentrates on repetitive lines and circles.

Chinese is entirely different. Its written signs, or characters, are meaning symbols, each functioning roughly as a single word does in English. Characters are also formed by assembling dots and lines, but there are more such elements with more varied shapes. Each element, a dot or a line, as a building block of Chinese characters, is called a stroke. In writing, strokes of various shapes are assembled in a two-dimensional space, first into components and then by combining components into characters. In the example in the above picture, the character 字 zì has two com-ponents, 宀 and 子, arranged in a top-down fashion. The component 宀 consists of three strokes, as does the other component 子. Generally speaking, the number of characters required for daily functions such as newspaper reading is three to four thousand. As meaning symbols, the characters have to be distinct enough for visual decoding. Therefore, they cannot all be simple in structure. Some are relatively sim-ple with a small number of strokes, while others can be quite complex with more than twenty or even thirty strokes. Each character has a unique internal structure. The components making up these characters, for example, can be arranged in a top to bottom, left to right, or even a more complex configuration.

In calligraphy, the soft and resilient writing brush is used to vary the shape and thickness of each stroke. This tool, combined with ink on absorbent paper, makes each character distinct. When characters are put together to form a text, additional techniques create coordination and interplay not only between adjacent characters, but also among characters that appear in different parts of a text. Instead of striving to produce a uniform look, Chinese calligraphers make every effort to keep charac-ters recurring in a text different from one another.

Generally speaking, Western calligraphy reflects an interest in ornamenting words on the page. It stresses perfection and rigidity; mastering exact duplication of letters is considered the pinnacle of the art. More modern works do overcome the traditional boundaries and allow for personal expression, but this is most often seen in high art and is hard to find from the average calligrapher. Thus calligraphy in the West is gen-erally considered a minor art that tends to curb spontaneity. Chinese calligraphy, by sharp contrast, is an art form in which variation is the key. The freedom of personal expression or personal emotion that emanates through the work is its goal.

The ability to reach this goal depends on the nature of Chinese writing, the writ-ing instruments, and the skill of the calligrapher. Together, these elements provide enormous opportunities for artistic expression. While creativity is the life of any art, the complex internal structure of Chinese characters and the unique writing instru-ments have allowed ample space in multiple dimensions for Chinese calligraphy to develop into a fine art whose core is deeply personal, heartfelt expression.

Another important aspect of Chinese calligraphy is the astounding variety of uses it serves. Western calligraphy is typically reserved for formal use such as in wed-ding invitations, certificates and awards, and other special documents. Its historical linkage with organized religion also places it outside the realm of ordinary human activity. In addition, its preindustrial origins and prevalence throughout medieval and early modern Europe visually relegate it to the past. All of this is in stark contrast to China’s continuous fascination with calligraphy, which is still a part of everyday' life.