Writing and Calligraphy in the Chinese Society

index | szakfordítások és publikációk

All languages serve the practical function of communication. In different cultures and societies, however, language and its roles are perceived differently. According to Jewish and Christian cultures, God created language (human speech). In Chinese culture, however, the origin of speech is never accounted for; instead, the historical emphasis has always been on writing. To the Chinese, the creation of language means the creation of Chinese characters. Credit for this inven-tion is given to a half-god, half-human figure called Cang Jie (倉頡), who lived about four thousand years ago. The ancient Chinese believed that Heaven had secret codes, which were revealed through natural phenomena. Only those with divine powers were endowed with the ability to break them. Cang Jie, who had four eyes, had this ability. He was able to interpret natural signs and to transcribe the shapes of natural objects (e.g., mountains, rivers, shadows of trees and plants, animal footprints, and bird scratches) into writing. Legend has it that when Cang Jie created written symbols, spirits howled in agony as the secrets of Heaven were revealed. Since then all Chinese, from emperors to ordinary farmers, have shared a tremendous awe for written symbols. They have venerated Cang Jie as the originator of Chinese written language. Today shrines to Cang Jie can be found in various locations in China. The one in Shanxi Province, not far from the tomb of the Yellow Emperor, the legendary ancestor of the Chinese people (ca. 2600 BCE), is at least 1,800 years old. Memorial ceremonies are held every year at both shrines.

Cang Jie (倉頡)

One reason for the great respect for the written word in China has to do with the longevity of Cang Jie’s invention: the written signs he created have been in continuous use throughout China’s history. This written language unites a people on a vast land who speak different, mutually unintelligible dialects. It is also the character set in which all of the classics of Chinese literature were written. Using these characters, the Chinese were the first to invent movable type around 1041 CE. It is estimated that, until the invention of movable type in the West, no civilization produced more written material than China. By the end of the fifteenth century CE, more books were written and reproduced in China than in all other countries of the world combined!

The central, indispensable role of the written language in China nurtured a reverence for written symbols that no other culture has yet surpassed. Written char-acters hold a sacred position, being much more than a useful tool for communica-tion. As we will see throughout this book, characters have been incised into shells of turtles and shoulder blades of oxen; they have been inscribed on pottery, bronze, iron, stone, and jade; they have been written on strips of bamboo, pieces of silk, and sheets of the world’s first paper. They are on ancestral worship tablets and for-tuneteller’s cards; they appear at building entrances and on doors for good luck. When new houses are built, inscriptions are put on crossbeams to repel evil spirits. Significant indoor areas or the central room in a traditional residence always have brush-written characters visible at a commanding height. Decorating such halls and rooms with calligraphy is a ubiquitous tradition in China, which should not be compared to the Western tradition of hanging framed biblical admonitions, printed in Gothic letters, on the wall of an alcove. The importance of the latter resides much more in its message, whereas that of the former is predominantly its visual beauty.

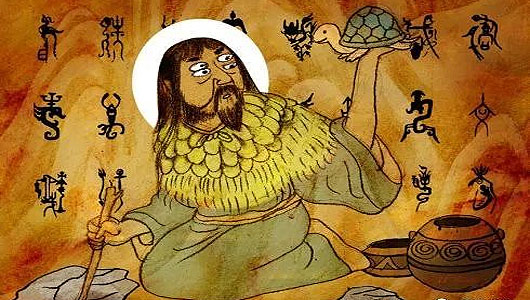

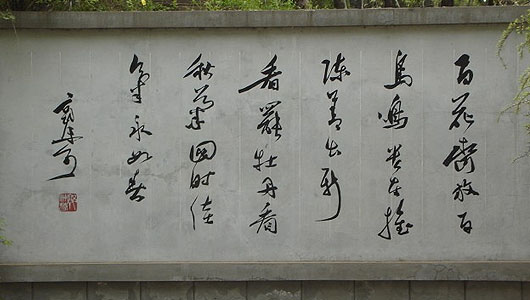

Written characters are also an integral part of public scenes in China. Simply by walking down the street, one can enjoy a feast of numerous calligraphic styles on street signs, shop banners, billboards, and in restaurants and parks. During festivities and important events, brush-written couplets are composed and put up for public display. There are marriage couplets for newlyweds, good-luck couplets for new babies, longevity couplets on elders’ birthdays, spring couplets for the New Year, and elegiac couplets for memorial services. Calligraphy works written in various styles can be purchased on the street or in shops and museums; these may feature characters, such as 福 fú, “blessings,” and 壽 shòu, “longevity,” written in more than one hundred ways.

Living room in a modern urban residence with a piece of calligraphy

Wallpaper in a restaurant with 福 (blessings) in various styles

Restaurant sign Brocaded Red Mansion 錦繡紅樓 in Small Seal Script

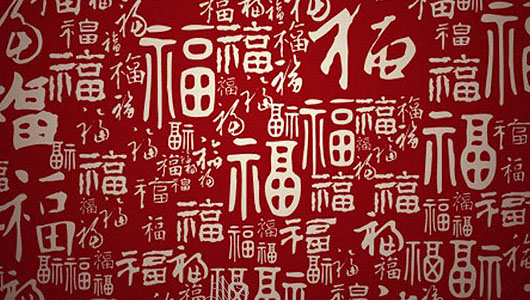

The decorative function of Chinese calligraphy is a common sight in China. At tourist attractions, writings of past emperors and calligraphy masters or famous sayings and poems written by famous calligraphers are engraved on rocks or wood to enhance the beauty of nature. They can even be found on sides of mountains, where huge characters are carved into stone cliffs for all to view and appreciate. The Forest of Monuments in the historic city of Xi’an and the inscriptions along the rocky paths of Mount Tai are the largest displays of Chinese calligraphy. Places well-known calligraphers visited and left such writing are historic landmarks protected by the government today.

The importance of writing in Chinese society and, more specifically, the im-portance of good handwriting are apparent to students of Chinese history. Before the hard pen and pencil were introduced to China from the West in the early twen-tieth century, the brush was the only writing tool. Brush writing was a skill every educated man had to master. In the seventh century CE, the imperial civil ser-vice examinations were introduced in China to determine who among the general population would be permitted to enter the government’s bureaucracy. Calligraphy was not only a subject that was tested, but also a means by which knowledge in other subject areas (including Confucian classics and composition) was exhibited. In theory at least, anyone, even a poor farmer’s son, could attain a powerful govern-ment post through mastery of the subjects on the exams. This new system standard-ized the curriculum throughout China and offered the only path for people with talent and ability to move up in society.

Daguan (Grand View) Peak inscribed wall at Mount Tai. Calligraphy written by emperors and famous calligraphers was carved into cliffs to praise the natural beauty and the scenery. The two large red characters on top left (meaning “peaks in clouds”) were the calligraphy of the Kangxi emperor (1654–1722) of the Qing dynasty. The text below was written by the Qianlong Emperor (1711–1799), also of the Qing dynasty

on Taimu Shan in front of a carved stone by NAMO AMITUOFO (南无阿弥陀佛)

Accordingly, success in the civil service examinations became the life dream of generations of young men, and calligraphy was virtually a stepping stone. From a very early age, students would start practic-ing calligraphy and studying the Confucian classics. For thirteen centuries, the civil service examinations were central to China’s political and cultural life. They created a powerful intelligentsia whose skills in composition and calligraphy were highly valued. Consequently, in traditional China, excellence in learning, superb hand-writing, and an official post were a common combination.

Calligraphy and poem by Guo Moruo (郭沫若, 1892-1978), a well-known modern Chinese scholar, displayed outside the Guo Moruo Museum in Beijing

This tradition is carried on in modern China. Today, during important events or official inspection tours, government officials often write or are asked to write words of encouragement and commemoration in calligraphy to be presented to the public. A person’s learning is judged, at least in part, by his or her handwriting. A scholar’s essay, however wise, is considered poor if the handwriting is inferior. Although the civil service examinations were abolished at the beginning of the twentieth century, China remains a society where good handwriting is uniquely valued. China’s rulers have played a role in promoting calligraphy. Numerous past emper-ors were masters of calligraphy and left their works for later generations to appreciate.

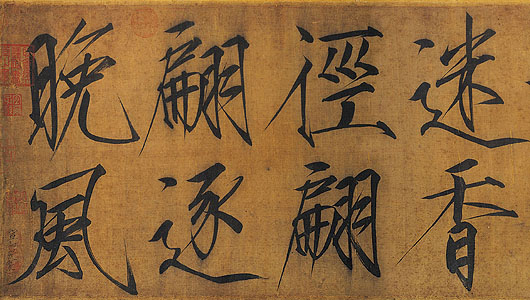

Writing takes place every minute of the day in every corner of the world, but in China it is elevated to a fine art that pervades all levels of society. The art of calligra-phy is held in the highest esteem, surpassing painting, sculpture, ceramics, and even poetry. Yet, Chinese calligraphy is more than an art. It is a national taste, nourished in everyone from childhood on, that has penetrated every aspect of Chinese life. In China it is believed that a person’s handwriting reveals education, self-discipline, and personality;

Slender Gold by Emperor Huizong of the Song dynasty. Collection of the National Palace Museum (Taipei)

... it measures cultural attainment and aesthetic sensitivities; and it even relates to physical appearance. Thus the instinct to judge or comment on a person’s handwriting is as common as the instinct to judge people’s appearance and personality. In a way, handwriting is like a person’s face: everyone tries to keep it at its best. For the same reason, good handwriting brings satisfaction, confidence, self-esteem, and respect.

In modern China, calligraphy is not only a regular part of the school curriculum; it is practiced by people of all ages and from all walks of life. Although the practical function of brush writing is diminishing in modern society, calligraphy remains a widely practiced amateur art for millions of Chinese—an enjoyable pastimeÂoutside of work and daily chores. Along with calligraphy clubs, associations, magazines, and local and national competitions at all levels, prominent newspapers also publish columns on Chinese calligraphy.

Visitors to China today often notice a unique cultural phenomenon: In every town and city, in the early morning when a new day is just starting, people, old and young, male and female, gather in parks or even on sidewalks to do morning exercises. Many bring a special brush tied to a stick and a bucket of water; then they find a quiet spot and start wielding their brushes on the pavement. A new name, “ground calligraphy” or “water calligraphy,” has been given to this new way of both practicing calligraphy and doing morning exercises. Medical research has indicated that regular, sustained practice of calligraphy may improve body functions and is thus a good way to keep fit.

Chinese brush writing once served as the primary means of written communication. During thousands of years of practice, it developed into a fine art. In modern Chinese society, because of its combination of artistic characteristics, cul-tural underpinnings, and health benefits, calligraphy continues to flourish and break new ground. Love for the written word is not only present among the literati and promoted by the government, but also deeply rooted in the populace. The art of calligraphy has also spread to nearby countries such as Japan and Korea, where it is practiced and studied with great enthusiasm.

Why is writing so important to the Chinese? What makes it special and different from the writing of other languages? To answer these questions, let’s look more close-ly at the nature of Chinese writing and then compare it with Western calligraphy.