The Formation of Chinese Characters

index | szakfordítások és publikációk

The distinct look of Chinese written signs has given rise to misconceptions, one being that Chinese is a pictographic script and that each symbol in Chinese writing is a picture of something. Even college students may fall into this trap. "How do you draw this character?" they ask, reluctant to use the word "write". Apparently, this misunderstanding arises because Chinese is not alphabetic. The written symbols do not directly relate to sounds. Rather, they are meaning symbols that sometimes have a connection with the shape of objects.

The Nature of Chinese Written Signs

In the Western world, since phoenician businessmen taught their method of writing to customers around the Mediterranean more than three thousand years ago, writing systems have been alphabetic—representing sounds of speech. Previously, however, writing throughout the world was no different from Chinese. Every-where, written expression was logographic—symbols represented words rather than sounds. Many logographic language symbols, especially in early writing, were pictographic (they resembled the physical appearance of the objects they represented). This was true for all ancient languages, including cuneiform (used in ancient Sumer, Assyria, and Babylonia), hieroglyphics (Egypt), and Chinese (China). A check on the origin of the English alphabet shows that the twenty-six letters evolved (with intermediate steps) from proto-Phoenician "pictographic" symbols. The letter "A", for example, began as the image of an ox’s head turned sideways. Now, however, the letter "A" and all the other symbols in the alpha-bet are sound symbols. Keep in mind that no language, even ancient languages, can be completely pictographic, because once a language system is in use, there have to be symbols that represent abstract ideas and indicate grammatical relations between words. Those symbols cannot be pictographic.

What distinguishes Chinese from the rest of the world’s ancient logographic languages is that Chinese logographic writing was not abandoned in favor of alphabetic writing. Instead, Chinese writing has remained logographic up to the present day. This is not to say that Chinese has not changed; in fact, although the writing system has never taken the revolutionary step of adopting an alphabetic scheme, primitive pictographs and logographs have gradually been refined and stylized into an intricate and highly sophisticated system.

The question of why Chinese has never adopted an alphabetic scheme would take an entire book to answer. What can be briefly mentioned here is that, geographically, China is very much isolated from the rest of the world by oceans to its east and mountains and deserts in the west. This separation was accompanied by the development of a high culture, early in Chinese history, that greatly influenced its surrounding areas. Chinese customs and Chinese characters in writing were adopted by many of its neighbors. But until the nineteenth century, only one major foreign influence had a broad impact on China: Buddhism, from India. Even so the Chinese writing system has never been affected. Having developed in a geographic vacuum and resisted foreign influences, the Chinese writing system remained purely indigenous by keeping its logographic nature.

Thus not only has the Chinese language been in continuous use for several millennia, Chinese written symbols still bear traces of their origins. A person today with only partial knowledge of classical Chinese grammar can still read classical literature written two thousand years ago. For English readers, whose language consists of words with origins in Anglo-Saxon, Norman French, Latin, and Greek, and who cannot read English texts written as recently as seven hun-dred years ago, the unbroken chain of an ancient written language elicits wonder and fascination.

Given that Chinese writing does not show pronunciation directly, how, then, are the writing symbols constructed? As stated earlier, the number of characters even for the most basic functions goes to thousands. These characters, however, are not a collection of unrelated arbitrary symbols. Analyses of characters since ancient times have indicated several major methods by which characters were formed.

This work was first done in the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) by a philologist named Xu Shen (許慎 ~58-147) in a book titled Shuo Wen Jie Zi 《說文解字》, or Analysis of Characters. Xu Shen divided all characters used in his day into two broad categories: single-component characters (such as mu (木), "tree") and multiple-component characters (such as lin (林), "woods", which combines two "tree" symbols into one character). Single-component characters are called "wen" (文) and multiple-compo-nent characters Zi (字). Hence, the literal translation of the title of Xu Shen’s book is "speaking of Wen and explanation of Zi." Six categories of characters were identified that reflect major principles of character formation and use. The book lists 9,353 characters plus 1,163 variant forms. It is believed to be the most comprehen-sive study of characters in use during that time.

Xu Shen (許慎 ~58-147)

Since the Han dynasty, the Chinese writing system has not changed much overall, nor have there been changes in the principal methods of character forma-tion, although the number of characters in use grew to about 47,000 in the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) and is well over 60,000 today. For more than 1,900 years, Xu Shen’s analysis in terms of six classes has remained an influential categorization method of Chinese characters, although alternative etymology theories have also been proposed.

Categories of Characters

Within Xu Shen’s Six Classes (六書), four (classes 1, 2, 3, and 5) have to do with the formation of characters. The other two regard character use. The sixth class, known as Zhuan Zhu (轉注) or "semantic transfer", will not be looked at in detail here because it involves disagreement among scholars, and examples are scarce. For people without knowledge of Chinese writing, the etymology of the examples for each category is quite interesting. They make useful mnemonic devices for learning some characters.

Pictographs

Many early written signs in Chinese originated from sketches of objects. Thus they bore a physical resemblance to the objects they represented, like pictures, which is why they are called pictographs. Typical pictographs are illustrated in this picture:

The evolution of pictographic characters

Apparently, the written signs in this picture were invented to represent physical objects in the world, and gradually they evolved from the original pictographic symbols into their modern forms by a process of simplification and abstraction, during which details were left out and curves were changed into straight lines. As a result, modern characters are far removed from their original pictures, although they sometimes still show traces of the objects they represent. Although these are the most frequently used examples of pictographic characters, modern people without any knowledge of Chinese characters, when seeing these symbols, would make no connection to their referents before the similarities were explained. The character "Ri" (日) which means "sun" for example, looks more like a window, while the character Yue (月) which means "moon", resembles a stepladder. Generally speaking, without knowing the meaning of these characters, one cannot decode them by merely looking.

Although pictographic characters are the best known type among people who are not very familiar with Chinese written signs, their number is much smaller than one might think. Even in the earliest writing we know of, the Shell and Bone Script (ca. 1400–ca. 1200 BCE), pictographic signs were a small portion of characters, about 23 percent. Even then the majority of written symbols did not depict physical shapes of objects. The decline of pictographic signs was well under way by the Han dynasty. When Xu Shen did his study based on Small Seal (小篆) characters, pictographic signs comprised only 4 percent of all Chinese characters.

In modern Chinese, even fewer characters show their pictographic origin clearly. A more common function of these "pictographic" signs today is to indicate the semantic category of a compound character.

Indicatives

An indicative is a character made by adding strokes to another symbol in order to indicate the new character’s meaning. For example:

Ren (刃), "blade." A dot is added to 刀 dao which means "knife." Dan (旦), "morning." A horizontal line is added underneath Ri (日) which means "sun" to show the time when the sun is just above the horizon. Ben (本), "root." A short line is added to Mu (木) which means "tree."

Semantic Compounds

Semantic compounds are constructed by combining two or more components that collectively contribute to the meaning of the new character. Examples are

Ming (明), "bright" which combines of Ri (日), "sun," and Yue (月), "moon." Kan (看), "look" has Shou (手), "hand" over Mu (目), "eye". Lin (林), "woods" shows two Mu (木) which means "tree". Sen (森), "forest" is composed of three Mu (木), "tree". Qiu (囚), "prison" is represented by a Ren (人), "person" in 囗, "confinement". :-)

The methods of character formation represented by pictographs, indicatives, and semantic compounds are all iconic. They are limited in that new signs have to be created for new words. As a result they could not meet the needs of a fast-developing society and its increasing demand for new written signs. In ad-dition, abstract ideas and grammatical terms (such as prepositions, conjunctions, and pronouns) were impossible to represent with pictographic signs. The solu-tion was to break away from iconic representation and to use existing written signs to phonetically represent the sounds of new words. This process is called "borrowing."

Borrowing

Borrowing in this context refers to the use of existing characters to represent ad-ditional new meanings. Two frequently used examples are:

Lai (來), originally a pictograph for "wheat." The written character with its pronunciation was later borrowed to mean "to come." In time, the borrowed meaning prevailed, and the original meaning of "wheat" died away. Qu (去), originally a pictograph for a cooking utensil. Later the character was borrowed to mean "to go." The borrowed mean-ing also prevailed, and the original meaning died away.

In cases such as 來 lái and 去 qù, only the borrowed meaning has survived in modern Chinese.

Semantic-Phonetic Compounds

Semantic-phonetic compounds are a hybrid category constructed by combining a meaning element and a sound element. This method of character formation thrived as a means to solve the ambiguity problem caused by borrowing. As can be easily seen, when a particular character is borrowed to mean more and more different things, sooner or later, the interpretation of the multiple-meaning writ-ten sign becomes a problem. To solve the problem and to allow borrowing to continue, a semantic element is added to indicate the specific meaning of the new character. This process led to the creation of semantic-phonetic compounds.

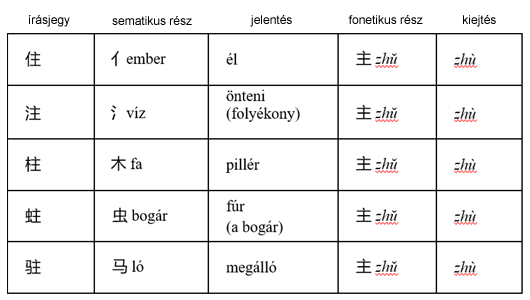

Thus, a semantic-phonetic compound has two components, one indicating meaning and the other pronunciation. Take Zhu (主), "host", as an example. In modern Chinese, the character is used as a phonetic element in more than ten semantic-phonetic compounds, five of which are shown in the table below. The five characters in the first column are pronounced exactly the same way, Zhu, although they are different in meaning. They share the same phonetic element, Zhu (主) which is the right-hand side of the characters. The signs on the left are semantic components, which offer some clue to the meaning of the characters.

The semantic elements, for example, 亻, "person" 氵, "water", and 木, "tree" are pictographs commonly known as "radicals." Their function is to hint at the meaning of the characters in which they appear. At the same time, they also group semantically related characters into classes. For example, all the characters with 亻, "person" as a component have to do, at least in theory, with a person or people; all the characters with 木, "tree" as a component have to do with wood or trees. Traditionally, Chinese characters are categorized under 214 radicals.

One way to organize characters in dictionaries is to group them under these radicals.

Lots of tables illustrate the combination of semantic and phonetic elements in the formation of characters. The vertical columns group characters by phonetic elements, and the horizontal rows group characters by semantic elements. In other words, characters in the same column have phonetic similarities and those in the same row share semantic features. The arrangement of the two elements in a semantic-phonetic compound can be left to right or top to bottom (as in 菁, 筒, and 苛). Other patterns not shown here include outside to inside, as in the character Guo (国), "country". Radicals may take any position in a character.

In modern Chinese, the majority of characters in the writing system belong to the category of semantic-phonetic compounds. From as early as the Han dynasty, this became the most productive method for creating new characters. It is worth noting, however, that there are problems with extensive reliance on semantic-phonetic characters. Languages change over time, and Chinese is no exception. Both the pronunciation and the meaning of characters are in a state of flux. While the written signs remain constant, over time sound change and semantic evolution have eroded the relationships between characters and their sound and semantic components, making it more and more difficult to deduce the meaning and pro-nunciation of a character from its written form. Now, as can be partially seen in table, phonetic elements do not indicate the pronunciation of the characters clearly and accurately; nor do semantic elements show the exact meaning of characters. In modern Chinese, the value of semantic-phonetic characters resides in the combination of these two types of information to determine a character’s meaning and pronunciation.

The Complexity and Developmental Sequence of the Categories

The five categories of characters described above represent three stages of de-velopment in character formation. The first stage is represented by pictographs, indicatives, and semantic compounds. At this stage, written signs were created based on a physical resemblance of some sort. This process also corresponds to an early mode of human cognition, perceiving the world through the senses. Of the three categories, pictographs are the simplest; indicatives and semantic compounds involve more complex and abstract concepts.

The second stage is phonetic borrowing. Initially, single-element characters such as Zhu (主), "host" were borrowed to represent additional meanings. As the multiple meanings of single characters became a source of enormous confusion, semantic elements were added to differentiate meanings more clearly, which led to the use of semantic-phonetic compounds.

The third stage combines semantic and phonetic information to create new characters. This is the highest stage of development, completed in the Han dynas-ty, about two thousand years ago, when the Chinese writing system reached maturity. No new method has appeared since then, although the existing categories of characters have grown and shrunk. In modern Chinese, more than 90 percent of characters in use are semantic-phonetic compounds; those that can be traced back to their pictographic origins comprise less than 3 percent.