The Process of the Chinese Calligraphy Exercise

For beginning students, learning to use a Chinese writing brush can be an awkward experience at first. The hand may feel clumsy because the brush is held differently than other writing instruments. You may feel like a child because even writing a straight line takes so much effort. The bristles are difficult to control, and it is easy to make foolish mistakes.

Learning Chinese calligraphy is more than learning to write with a Chinese brush. It is a sophisticated form of visual, tactile, and mental training that demands

- a calm and relaxed mind,

- correct posture,

- concentration on the task at hand,

- coordination of mind and body, and

- patience.

In China, traditional teaching and learning practice includes a stage of tracing and copying to help the learner acquire these abilities.

The Importance of Tracing and Copying

At the beginning stage, learners embark upon the task of acquiring a number of new skills: how to handle the brush to produce various strokes, the pressure to apply and the proper amount of ink to keep in the brush, and the speed with which the hand moves the brush. Tracing and copying from models is always the first step, first faithfully stroke by stroke, and then character by character until the spirit of the art penetrates the student’s mind. Traditional Chinese training methods have always put a strong emphasis on imitation and copying. This is often puzzling to Westerners, who are used to being urged to express themselves and avoid imitation.

In Chinese calligraphy, in fact in Chinese art in general, imitation and copying are considered virtues. Good copies and imitations are appreciated as well as the originals. This is why, over the course of the long history of Chinese calligraphy and painting, old masters’ works have constantly been copied. One often sees works that openly acknowledge being “an imitation of so-and-so.” In fact, many of the famous early calligraphy works extant today are copies rather than originals.

It is believed that a beginner must first learn the essentials from masters of the past before trying to develop an individual style. Tracing and copying, like gathering information by reading books, are shortcuts or aids in learning the fundamentals and establishing a solid foundation. For a schoolchild, learning may eventually happen without reading books, but the discovery process will be much longer. In calligra-phy learning imitation is also a process leading to discovery, a discovery of the good qualities in the model and the techniques used to produce them, a discovery of one’s own limitations so that efforts can be made to overcome them, and a discovery of one’s options in individual freedom without violating general principles. It is also through imitation and copying that the tradition of the art is carried on. Lack of sufficient training in the necessary principles and techniques will result in chaos.

Tracing and copying also help to develop the coordination of mind and body. When one is an experienced artist, the mind leads the brush; that is, the mind knows what to do, and the body is able to implement the plan. Such coordination and confidence, so important for the creation of art, are often difficult for begin-ning learners. All too often, writing is started without a plan for how to proceed so that, in the middle of a stroke, the question may pop up: “What am I supposed to do now?” Writing is a productive process with several components, from projecting an image of the end product in your mind, to knowing the creative steps leading to the end product, to having the skills to faithfully produce the specific effects in your mind. Tracing and copying are techniques that break down the components and focus on training in one area at a time. A three-step procedure is followed to help learners gain more and more control gradually, from skills of the brush, to execution following a model, and finally to a full creative agenda.

Trilogy in Training

The training procedure process consists of three steps.

Tracing

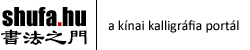

Tracing means writing over the characters in your copybook. There are two forms of tracing. In outline tracing the outline of a character is printed on paper. The learner fills the outline with black ink. Before model sheets with the printed outline of characters became available, students traced the outline of the characters manually with pencil, pen, or the fine tip of a brush and then filled in the outlines with black ink. Even today, devoted students still do this, as tracing the outline of characters manually is considered a good way to study the structure and details of model characters before writing them with a brush. The other form of tracing, red tracing, is writing over characters already printed in red with black ink.

Outline tracing and Red tracing (shown in grey here)

In tracing, since you can see exactly what your end product should look like, your mind can concentrate on building the skills to produce the effect. Your goal at this stage, therefore, is to learn to maneuver the brush to produce the shape of brush strokes already shown on paper. The focus of tracing is mainly on the shape of strokes. You should try to cover the size and shape of the strokes completely and exactly as shown, no more and no less.

Copying

When copying, the model is placed to one side and then imitated in a two-step procedure. First, look at the model and try to keep the details in your mind. Then, produce what you have in your mind on paper. The challenge at this stage, then, is to observe the important features of the model and faithfully reproduce them. To assist learners in this process, a grid is usually laid both over the model characters and in your writing space. Gazing at the grid that divides the model into small sec-tions will help you gauge the position, shape, and size of the model. Then, using the writing space with the same grid pattern, you will know exactly where a stroke should start and end. This helps in positioning the strokes and controlling the size of the characters you write.

The focus in copying, as the second step in learning, should be mainly on the structure of characters. Note that characters only take up about 80 percent of the square space; don’t forget to leave “breathing space” around each character.

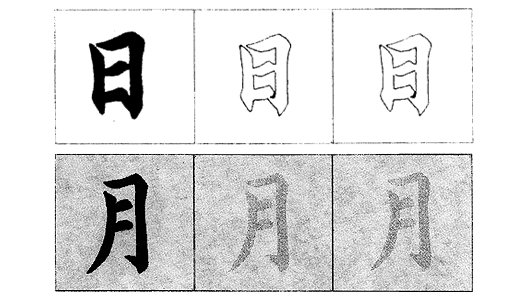

We are going to use two grid patterns. First is the eight-cell pattern that divides a character space like a pie. Because this grid resembles the Chinese character 米 mĭ, it is called the mĭ-grid in Chinese (米字格 mizige). The second, the square-grid pattern (方格 fangge), defines the space for a character without further dividing it. The eight-cell grid pattern is for beginners, and the square grid is for people with some experience. There are other commonly used grid patterns, for example, the nine-cell grid (九宮格 jiugongge), which divides the space for a char-acter horizontally and vertically.

Grid patterns for copying

Copying is first done stroke by stroke and then character by character. Carefully studying the model before writing remains an indispensable step. Tracing or copy-ing without thinking, even dozens of times, leads nowhere. It is not the number of times the model is practiced that counts, but the quality of the writing. Before writ-ing a stroke, make sure you know by heart exactly how it should be written from the moment the brush touches the paper to the moment it is lifted. Each stroke must be made in one continuous movement. Once you start, you cannot turn your eye to the model to see how you should proceed, because doing so will slow down your brush, and your stroke will show marks of hesitation. Similarly, after you com-plete a stroke, you cannot go back to touch it up. If you do, the corrected area will show traces once the ink is dry, and the entire piece will be spoiled.

Study your model character to see the correct sequence for writing the strokes, the position of the strokes, their size compared to other strokes in the same charac-ter, how the strokes are put together to form components, and how the components are put together to form the character. After you have copied the character, compare the character you have written with the model to see the differences and determine what needs to be done to make your writing better. Then, write the same character again. There should be improvement each time you repeat the same character.

Traditionally, characters in the Regular Script are divided into three different sizes for practice: The large size (大楷, dakai), which is about four square inches or more for each character, the midsize (中楷 zhongkai), about two square inches, and the small size (小楷 xiaokai), about half a square inch or less for each character. The grid size for the brush-writing exercises in this book is about two square inches, that for midsize characters.

Free Writing

The third stage is for those who have gained confidence in the structure and size of characters and are ready to write without using models. An experienced writer, having learned the basics by tracing and copying, develops a signature style that is personal but, still, is usually based on or influenced by a calligraphy master of the past. Nonetheless, even an experienced writer makes plans before actually picking up the brush to write.

Since imitating models is such an important step in learning, a good model must be chosen. This is why calligraphy learners over the centuries have always used works of renowned calligraphy masters such as Yan Zhenqing and Liu Gongquan as models. Switching between models should be avoided. In this book, we use the writing of Wang Xizhi, the calligraphy “sage” of the Jin dynasty. When tracing and copying, try your best to capture the good qualities of your model. You will profit from this practice by avoiding the pitfalls old masters have uncovered. This is an efficient way to shorten the path to good writing.

Getting Ready to Write

Prepare Your Mind and Your Writing Space

Start writing with a quiet and relaxed mind. One has to be calm and able to focus and concentrate. There is no point writing in a hurry or when your mind is not ready. You also need a comfortable space on the table so that you can sit in the correct posture and move your arms freely without bumping into anything. If you copy from a model book, put your model close by so that you can easily see it (usually on the left of the writing paper if you use your right hand to write). Use your ink stone as a paperweight to keep the top of your writing paper in place.

Posture - Body

Unlike Western painting with its vertical or tilted canvas, Chinese calligraphy is mostly done on a horizontal, flat surface. Beginners should write at a table, although experienced writers may also write on the floor.

The weight of your body should be kept forward, about two or three inches away from the table. Your center of gravity should be the lower abdomen, which is also the core of your torso. During writing, no matter how your arms move, this should be the center that generates force that passes through the brush to the char-acters. When both feet are placed solidly on the floor in front of you, you will be sitting in the position known as the “horse stand.” This posture helps to bring the center of gravity forward and gives you the flexibility to control the movement of your arms. Both your elbows should be on the table, away from your body. Do not lean too much over the table, and do not tilt your head too far sideways.

Posture - Wrist

The size of the characters to be written governs the position of the wrist. Usually for a beginner, for practical purposes, your wrist should be resting on the table. This is so especially when writing relatively small characters of one to two square inches, because such writing only requires the manipulation of the brush by finger and wrist movements. Training in brush writing usually starts with characters of this size to develop finger maneuvering skills. As an alternative, some people cushion their wrist with their nonwriting hand, palm down. For more experienced writers, the “lifted wrist” position can be used to obtain greater freedom and particularly for larger characters. In this posture, the wrist is lifted one to two inches off the table, but the elbow should be touching the table.

The “suspended wrist” position, in which both the wrist and elbow are lifted, is the most sophisticated. This is for writing characters of larger sizes.

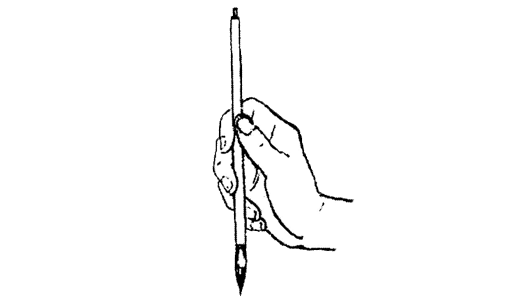

Posture - Writing Hand

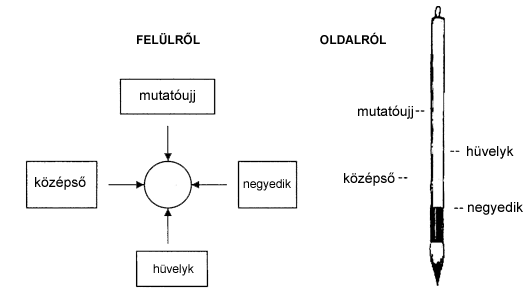

Keep your thumb pointing up and all the other fingertips pointing down. The way you handle your brush is of the utmost importance. Owing to the nature of the Chinese writing brush, the way you hold it will affect the quality of your strokes. As shown in Figure 2.7, the brush is held upright. Your thumb should be tilted with the nail pointing up; all the other fingertips should be pointing down. Your grip on the brush stem should be comfortable and flexible, similar to the way a dart is held before throwing.

Follow these four principles:

- Your palm should be loose and hollow, curved enough to hold a small egg. If you squeeze your fingers too tightly toward your palm, you lose flexibility.

- All your fingers should be involved in controlling and maneuvering the brush. Refer to this picture for finger positions and height.

Standard brush grip

The thumb and the forefinger are responsible for holding the brush at the correct height, and the middle finger gently pushes the brush inward (toward the palm). The fourth finger supplies pressure onto the other side of the brush, to counterbalance the inward pressure from the middle finger. The little finger should assist the fourth finger naturally but should not touch the brush, the palm, or the paper when writing.

- Both of your forearms should be kept level with your elbows on the table, to help with brush control. Do not drop your elbow down from the edge of the table.

- For maximum flexibility, all muscles directly involved in writing should be relaxed—this includes your fingers, wrists, arms, and shoulders. Be careful not to tense your neck either. Strained muscles and a tight grip limit movement, the hand is more likely to shake, and you will become fatigued more easily.

Posture - Brush

When writing, the brush stem should be kept vertical most of the time. Concen-trate your mind on the bristles, whose impact is strongest at the tip. You will rarely write with more than one-third of the brush at the tip. The upper two-thirds of the bristles act as an ink reservoir so that you can finish several strokes before re-charging your brush with ink. To deposit ink into this reservoir, the brush should be fully saturated. Saturation also stabilizes the spine of the brush and holds the hair together. If only the tip of your brush is dipped into ink, the bristles will become dry and split too soon.

Finger positions

The brush operates most effectively when all the hairs are relatively parallel. The easiest way to maintain this alignment is to avoid pressing down too hard on the paper. The correct amount of pressure causes the bristles to bend but does not crush their elastic spring. If the brush becomes bent and twisted, readjust it by dipping it back into the ink or by brushing it lightly against the side of the ink stone.

Posture - Paper

The paper for writing should be placed straight on the table in such a way that the bottom edge of the paper is parallel with the edge of the table. This may be difficult at first for some learners who are used to writing English with the paper turned sideways. Doing that when writing Chinese with a brush would cause you to lose your ability to judge, for example, whether your vertical lines are going straight down as required.

Posture - Breathing

Write with controlled and continuous exhalation. There is no need to hold your breath when you write. Breathe smoothly with the brush, exhaling as you write and inhaling when the brush is between strokes. It is difficult to write a strong and steady line while inhaling. Become calm before writing. There is no point in writ-ing in a rush. Also, do not overconcentrate, as this will make you stiff, tense, and tired.

Posture - Eyes

Look at your character as you are writing it. Whenever your brush is moving on paper, your eyes should be fixed on your writing. A common beginner’s error is to look back and forth between your model and your own writing while the brush is moving. This movement creates hesitant strokes, and the lines may also swell as you look away and your writing slows down. To avoid these problems, make sure you know by heart how to write a stroke from the beginning to the end and its exact position in a character before you put your brush to the paper so that you do not have to look at your model in the middle of writing the stroke.

Posture - The Free Hand

Use the free hand as paperweight. Lay the elbow of your free arm on the table, and use the fingertips of your free hand to hold the paper in place when writing. Hold the paper at the top when writing a vertical line and at its side edge when writing a horizontal line.

Moisture, Pressure, and Speed

Three important, constant concerns during writing are moisture, pressure, and speed.

Moisture

The brush should be slightly damp before it is dipped into the ink. As you dip, first give the bristles a chance to absorb as much ink as they can, and then gently squeeze out excess ink by sliding the tuft against the edge of the well of the ink stone. Do not apply too much pressure to the bristles as you slide, as that will break the ink reservoir in the brush center and overly drain it. Proper dipping and squeezing of excess ink will allow all the hairs in the brush, especially those in the center, to be involved in the management of ink in writing. A brush with a dry center will easily split, which in turn will make it impossible to form a solid line on paper. The ab-sorption and draining of ink into and from the brush is like a person’s inhaling and exhaling: a large vital capacity and proper coordination are essential for prolonged, smooth movements.

How much ink should you have in the brush before writing? If you can see ink accumulating at the tip of your brush, you have too much. However, you need enough ink to write at least a couple of strokes before the brush runs dry. A little trial and error will help you develop good instincts about this. Remember, when writing the Regular Script, characters in the same piece of work should look the same in terms of the amount of ink used. Even in modern styles, ink variations are by design rather than by accident. Therefore, control of ink is among the first things to be learned and experimented with in brush writing.

Try to start a stroke with a straight brush and the right amount of ink. That is, no hair is bent or sticking out, and the bristles are straightened and form a point at the tip. After writing a couple of strokes, if the bristles are bent and/or split, you should straighten them out on your ink stone. This is also an opportunity to re-charge your brush with more ink.

Pressure

Pressure is the amount of force employed to press the brush down on the paper. The harder you press, the wider the line. Because calligraphy brushes are so flexible, pressure control is the most important and yet difficult skill to master. The harder you press down, the more difficult it becomes for the brush to maintain its original resilient strength. Once a tuft of hairs is distorted, it needs to be fixed on the ink stone to regain its elastic power.

Speed

The speed of the brush, another important concern, is determined by a number of factors: the script that is chosen, the thickness of the desired strokes, and the amount of ink in the brush. When writing, the brush will discharge ink as long as it remains in contact with the paper. To avoid blotting, the brush must be kept in constant motion. Varied speed combined with the flow of ink produces visual effects. Mov-ing too fast produces a hasty line; the strokes will not look solid enough. When the brush is moving too slowly, the line will show signs of hesitation; the strokes may also run or bleed. In general, a wet brush should move more quickly and a dry brush more slowly to give the right amount of tone to the stroke. Also, speed up on straight lines and slow down on curves and at corners.

The control of moisture, pressure, and speed are important skills to acquire. It takes a great deal of experimentation and practice, as you begin writing, to put these skills together to produce desired line quality. The next three chapters contain detailed descriptions of individual strokes and the techniques involved in writing them.