The Yin and Yang of Chinese Calligraphy

vissza | a kalligráfia gyakorlása

The fundamental philosophical principle of yin and yang is reflected in every aspect of Chinese calligraphy. This chapter introduces that principle. It also covers the ap-preciation of calligraphy works and the relationship of calligraphy and health.

Diversity in Harmony

The study of Chinese calligraphy is not only a study of Chinese writing. In many ways, it is also a study of Chinese philosophy and the Chinese worldview. Aesthetic principles and standards are rooted in cultural and philosophical tenets, and Confucianism and Daoism form the basis of Chinese culture. Of the two Daoism has the stronger influence on art. It is no exaggeration to say that Daoism, from its place at the core of Chinese culture, is the spirit of Chinese art. Many characteristics of Chinese calligraphy reflect Daoist principles.

Dao literally means "way", the way of anything and everything in the universe. It is the way things come into being, the way they are organized, and the way they move about, each in its prescribed manner. Thus the notion of Dao can be understood as the overall organizing principle: everything has its own Dao; together, theentire universe has the universal Dao. Any being, existence, motion, or force is a manifestation of Dao—hence its power.

Studies of the development of cultures have found that the beginning of human cognition is marked by perceiving and categorizing things in the world as pairs of opposites, such as light and darkness, male and female, life and death, good and evil, sun and moon, old and young. Binary oppositions are a basic way by which ideas and concepts are structured. Claude Lévi-Strauss, the well-known anthropologist, observed that, from the very start, human visual perception has made use of binary oppositions such as up/down, high/low, and inside/outside; objects in the sur-rounding world, such as animals and trees, were also categorized based on a series of oppositions. Thus, from humankind’s earliest days, these most basic concepts have been used for the perception and understanding of the world around us.2 In modern times, the concept of binary thinking remains deeply ingrained in every aspect of daily life, from the design of electrical switches with on/off positions, to the yes/ no questions we answer every day, to the digital principles behind the design of a computer.

The Chinese are no exception in this respect. To them, the world consists of and operates on two great powers that are opposing in nature: yin, similar to a negative force in Western terms; and yang, analogous to a positive one. These two concepts are represented in the Daoist symbol known as the Great Ultimate.

Yin and yang are two poles between which all manifestation takes place. There is, however, a major difference in the Chinese view of these opposites from the metaphors of Western culture, in which oppositions are always in conflict. Light is at war with darkness, good with evil, the positive with the nega-tive, and so forth; they are pitted against each other and compete with each other for dominance.ÂIn the Chinese view, by contrast, the two fundamentally different forces are not in opposition but in perfect harmony. They complement each other and come together to form a whole. This philosophy is illustrated by the Great Ul-timate, which simultaneously represents duality and unity. One member is integral to the other and cannot exist without the other: such is the Daoist philosophy of the unity of opposites. The basic aim of Dao is attaining balance and harmony between the yin and the yang.3 Because there cannot be yang without yin, and vice versa, the art of life is not seen as holding to one and banishing the other, but rather as keeping the two in balance.

The Chinese have emphasized such harmony since ancient times. To them, har-mony has consistently been paired with diversity. Yin and yang are the two basic op-posing forces in the universe, but they are not hostile toward each other. Their union is essential for creation; they also work together for the well-being of everything. Things are in a good state if there is a good balance of the two. Therefore, the Chinese concept of yin and yang is not a concept of oppositions, but rather one of polarity.

The Great Ultimate symbol also has the appearance of a spiral galaxy, implying that all living things are constantly in cyclic motion. The energy source causing the motion is understood to be the breath of Dao, called Qi, or "life force." For example, one may see yang as the sunny side of a mountain or as dawn, and yin as the shady side of a mountain or twilight. These phenomena may differ in ap-pearance, but they are caused by the same energy source. As time progresses, yin becomes yang and yang becomes yin. Nothing stays the same all the time. By the same principle, all other things in the world—such as wars and wealth, births and deaths—come and go in everlasting cycles.

Dialectics in the Art of Calligraphy

The Daoist philosophy of yin and yang and the dialectic of diversity within unity have nurtured and fundamentally determined the character of the art of calligraphy.5 The pure contrast of black writing on a white background is a perfect example. From classical calligraphy treatises to modern-day copy models, descriptions of the techniques of calligraphy are based on elaborations of a full range of contrasting concepts. Such concepts along with classical wisdom are the foundation of the aes-thetics of Chinese calligraphy.6 Jin Kaicheng and Wang Yuechuan, for example, list twenty pairs of opposing concepts to illustrate the aesthetic dimensions of Chinese calligraphic art, including square (方 fang) versus round (圓 yuan), curved (曲 qu) versus straight (直 zhia), skillful (巧 qiao) versus awkward (拙 zhuo), elegant (雅 ya) versus unrefined (俗 ss), large (大 da) versus small (小 xiao), guest (賓 bin) versus host (主 zhua), and so forth. In writing practice, the artist manipulates and elabo-rates on the balance between opposites, emphasizing diversity within parts and the harmony or unity of the whole.

The yin-yang philosophy and dialectics are so fundamental to Chinese thinking that they are reflected in the vocabulary of the language. In Chinese, a group of ab-stract nouns is formed by compounding two characters of opposite meanings; each of these nouns specifies a dimension of variation. For example, 輕重 qingzhong, literally "light-heavy," means "weight"; 疾徐 jīxú, literally "fast-slow", means "speed"; 長短 changduan, "long-short", means "length", and so on. These nouns are frequently used to describe the techniques of calligraphy.

In calligraphy, these contrasts may become the basis for artistic expression. The most fundamental ones, such as "lift-press" and "thick-thin," are used in virtually every step of writing. The identification of writing styles as wild, pretty, powerful, delicate, or elegant is often based on these concepts. For example, more rounded strokes are generally thought to constitute a graceful style, while squarer strokes are believed to suggest power and strength. Characters with concealed tips look more reserved, while those with more revealed tips are outgoing and more expres-sive. These words and concepts reveal the relationship of writing techniques and aesthetic values to Daoist philosophy. In writing practice, the contrast and unity of opposites in various dimensions create contour and rhythm of movement.

Rhythm in calligraphy refers to various effects such as dry and wet, or light and heavy, created by the contrasting techniques. When a piece of writing has rhythm and a harmonious combination of elements, it has an innate flowing vitality that is of primary importance to the artistic quality of a piece. Rhythmic vitality gives the piece life, spirit, vigor, and the power of expression. With it, a piece is alive; otherwise, it looks dead. The beauty of Chinese calligraphy is essentially the beauty of plastic movement, like the coordinated movements of a skillfully composed dance: impulse, momentum, momentary poise, and the in-terplay of active forces combine to form a balanced whole. The effect of rhythmic vitality rests on the writer’s artistic mind as well as training in basic techniques and composition skills.

Rhythm can be found in a single brush stroke, a character, or in an entire composition. How strong the rhythm is depends on the degree of contrasts and their in-tervals. Generally speaking, Running and Cursive styles have stronger rhythm than the more traditional scripts. This is why many artists favor these two styles. When a piece is created with the vital forces of life and rhythm, the result is fresh in spirit and pleasing to the eye.

exert its vigor. Without the Daoist principle of diversity in harmony, there would be no Chinese calligraphy. Chinese calligraphy is often likened to Chinese Zen in that it does not lend itself very well to words and can only be experienced and perceived through the senses.

The way of calligraphy and the way of nature, although differ in scope, share similar principles. Calligraphy best illustrates Daoist philosophy when the brush embodies, expresses, and magnifies the power of the Dao. Thus, an adequate un-derstanding of the concept of yin and yang and its manifestations in calligraphy, and how various techniques are implemented to create contrast and unity in writing, is essential to your grasp of the core of the art.

Appreciation of Calligraphy

Beginning learners of calligraphy often ask, "What is good writing?" and "How can you tell?" Unfortunately, there are no simple answers to these questions. Chinese calligraphy continues to hold a special position in art because of the strong aesthetic impact created by its layout, its space dynamics, its black and white contrast, the quality of its strokes, and its coordination of dots and lines. The evaluation of callig-raphy has to take all these things into consideration. Below we will look at a general procedure for appreciating a calligraphy piece. This procedure is divided into stages that illustrate the dimensions in which calligraphy works may vary.

A good metaphor for the appreciation of a calligraphy piece is that it is like meeting a person for the first time: A general impression is formed first, followed by more detailed observations.

A general impression starts from first sight. This can usually be achieved fairly quickly. Aesthetic judgment at this point includes the identification of style. The viewer forms an initial impression: for example, the style of writing is wild, pretty, powerful, delicate, or elegant. Based on this impression, assumptions can be formed about the writer’s personality, interests, and even morals. It is believed that, since calligraphy is a highly individualized art, writing offers a glimpse of the heart. In Chinese calligraphy, insight into the ability to gain the writer’s personal traits is considered one area of aesthetic judgment.8 Two pieces of writing may be equally good but convey different feelings.

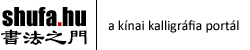

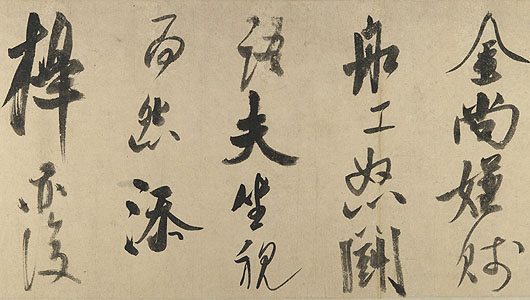

In comparison, is a piece written by Zhao Mengfu (赵孟頫, 1254–1322) of the Yuan dynasty. The style is more tactful, which is likely to indicate that the cal-ligrapher was a more sophisticated and modest man.

Mi Fu's (米黻, 1051–1107) Running Style. Collection of the National Palace Museum

Zhao Mengfu's (赵孟頫, 1254–1322) Running Style. Collection of the National Palace Museum

When a learner chooses a certain style as a model, the choice itself may reveal, in addition to personal taste, that the learner and the writer of the model have simi-lar personal traits. Listen to your heart when choosing a model. When following a model that you have a genuine liking for, you will be able to write better.

Overall composition and spatial arrangement also play a significant role in the initial impression. The main piece of writing must be well balanced by the place-ment of the seals, signature, and other elements written along the side. These ele-ments are to complement, but not overwhelm, the main writing.

After the general impression, the viewer starts a closer examination of brush-work and character writing. This second stage focuses on the techniques of writing. Knowledge of Chinese scripts and calligraphy is required at this stage. The viewer observes what brush techniques are used when creating a particular style. Impor-tant qualities to look for include the strength of strokes and texture in writing. A natural movement of energy is the life force that makes a piece lively. The viewer will observe whether the lines flow naturally with rhythm and vitality, whether the characters are well balanced, and whether they cooperate with one another with no harshness or discord. While doing this, the viewer imagines how the writing was produced by the brush from the beginning to the end. This adds great interest and enjoyment to the process.

The third stage involves an evaluation of the content or the theme of writing, its significance, and the atmosphere the piece produces. This evaluation includes not only the main text, but also inscriptions as well as the red seals and the suit-ability of script and style to the content of the work. From there, the viewer would go further to pursue a spiritual understanding of the work. This includes going beyond the form (the written lines) to understand the connotative meaning of the work and how the work connects or reveals aesthetic principles at a more abstract level. The viewer may also use imagination and association to create sympathy and response with the artist and the work at the spiritual level. Calligraphy is different from painting in that symbols of language are not direct physical images; they are abstract linguistic symbols that create meaning indirectly. The abstractness permits a great deal of potential in implication and interpretation.

As we can see, the three stages described above are at three distinct levels. The first stage can be achieved by the general public, with or without the knowledge of the Chinese language or calligraphy. It is like viewing a painting; a general impres-sion can be formed without appealing to specialized knowledge. The second stage is more technical and artistic. If a piece receives a positive rating by a knowledgeable viewer at this stage, it is most likely good writing. The third stage moves beyond the technical details into the realm of imagery association and abstract thinking. The aesthetics of Chinese calligraphy typically emphasizes this area. Thus the apprecia-tion at this level requires not only an artistic mind in both the viewer as well as the writer, but also solid background in Chinese culture, including philosophy, aesthet-ics, literature, and painting.

A piece of calligraphy is a piece of artwork. Whether there is communication be-tween the artist and the viewer and how much communication there is depends not only on the quality of the work, but also on the knowledge of the viewer. The more a viewer knows about calligraphy, the more he or she will get out of a piece. Thus, as a learner, the best way to refine your taste is to acquire background knowledge, wide exposure to the classics and calligraphy works, and to practice brush writing constantly. When you know what to look for, it opens up an entirely new world.

Chinese Calligraphy and Health

Chinese calligraphy is not only an enjoyment; it is also an effective way of keeping fit. In the Chinese way of life, cultivation is a goal that can be achieved through contemplation and concentration. Calligraphy is an ideal means to achieve this goal because it not only requires peace of mind and concentration, it also reinforces them during writing.

Calligraphy is a mental exercise. In modern society people live a busy life, over-wrought and exhausted by worries, anxiety, job pressure, appointments, and respon-sibilities. Various stresses cause the human body to release hormones that produce physiological responses such as shallow breathing and muscle tension. This stress, in turn, reinforces physically constricted conditions and perpetuates a vicious cycle. In Chinese medicine, it is believed that the seven major types of human emotions (âjoy, anger, melancholy, brooding, sorrow, fear, and shock) produce negative energy that accumulates in the body and causes disease. Suppressing emotions only makes things worse. Calligraphy is a moderate, healthy way to express emotions and re-lease blocked energy. It provides a channel to disperse negative buildup in the body, breaking the cycle and helping the busy mind to quiet down.

In East Asia, calligraphy is also practiced to mold one’s temperament and to cultivate one’s mind. Even before writing starts, a writer typically initiates an effort to calm down by letting go of daily worries and concerns and cutting off interfer-ence from the outside world. During writing, the writer refrains from talking and concentrates on the task at hand. By so doing, he or she is able to project the charac-ters in his or her mind accurately onto the paper through precise muscle and brush control. At the same time, the writing process also exerts a stabilizing influence on the writer’s mind, resulting in an even more transcendent sense of peace and clarity of thought. Thus calligraphy is commonly recognized as an effective way to remove anxiety and discover calmness and emotional grace. This is why in East Asian films scenes of calligraphy writing are often shown while the protagonists are making important decisions.

Calligraphy is also a light, soothing form of physical exercise, very different from strenuous workouts such as running or weight lifting. Writing involves almost every part of the body, from the fingers and shoulders to the back muscles and the muscles involved in breathing. Similar to Taiji, calligraphy is based on a typical Chinese philosophy that emphasizes moderation and detachment. Through slow, moderate movements, the energy generated in the lower chakras passes through the writer’s back, shoulders, arms, wrists, palms, and fingers, onward to the brush tip and, fi-nally, is projected onto the paper. This process encourages a balance between the brain’s arousal and control mechanisms, increases blood circulation and the vitality of blood cells, and thereby slows aging.

The function of calligraphy as a way to keep fit has a physiological basis. Be-cause the writing brush has a soft tip, its control requires more attention, vigilance, and accuracy than any other writing tool. Carelessness or interference from the surrounding environment will affect the quality of writing; therefore, control over any possible interference, including natural bodily rhythms such as breathing and the heartbeat, is crucial to creating optimal conditions for writing. Theories of cal-ligraphy never fail to emphasize the importance of calming down before writing, concentration, and breath control as the brush moves across the paper.

Physiological analysis indicates that the high degree of concentration required in brush writing causes significant changes in the writer’s physical responses. For example, the initiation of writing is usually accompanied by a decrease in heart rate and lowered blood pressure. When a high degree of concentration is reached, the heart rate significantly decelerates and blood pressure drops significantly.9 These responses are similar to those created by meditation with one major difference: Meditation seeks tranquillity in a state of rest, whereas calligraphy seeks tranquillity in motion. This contrast is a perfect example of the Daoist principle of harmoniz-ing opposites. When the body is relaxed in the motion of writing and the mind is at ease, the creative spirit takes flight into the formation and expression of beautiful ideas. This brings about a satisfaction and contentment of artistic creation that can-not be found in meditation.

The psychological and physiological activities that occur during calligraphy writ-ing were noted by the Chinese as early as in the Tang dynasty. Prolonged practice of calligraphy can play a significant role in keeping one fit and improving one’s health. This explains the well-known fact that, in traditional China, most calligraphers lived to an age well beyond the average life span. In contemporary China, with the upsurge in promoting traditional Chinese culture and public health, a new form of Chinese calligraphy has emerged, the so-called ground calligraphy mentioned in Chapter 1. This form of calligraphy is practiced early in the morning, in the fresh open air, mainly as physical exercise. Because its purpose is not to create art, it is done with simple instruments and the most basic writing material. It can also be done as a group activity, during which participants enjoy each other’s company and exchange ideas and opinions about writing. Because of its gentle, moderate nature, ground writing is a physical exercise most popular among elderly retirees. As a way to keep fit for longevity, it is a new way in which the traditional art form has adapted to the modern era.