Lanting Xu (Az Orcidea Pavilon Előszava) 《蘭亭序》

index | publikációk | facebook oldalunk

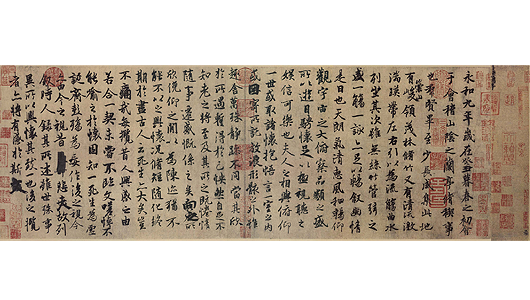

The Lanting Xu (Preface of the Orchid Pavilion) 《蘭亭序》or Lanting ji Xu 《蘭亭集序》is a famous work of calligraphy by Wang Xizhi (王羲之, 301-363), composed in the 353 CE. Written in elegant semi-cursive script and underpinned by deep philosophical thinking, it is among the best known and often copied pieces of calligraphy in Chinese history and also a famous piece of Chinese literature. It is revered as the best running calligraphy (天下第一行書). Wang Xizhi is respected as Shu Sheng (書聖), ‘Sage of Calligraphy’ or ‘Super Master of Calligraphy’.

Lanting Xu contains 28 vertical lines and 324 characters.

Lanting Xu (Orhidea Pavilon Előszava) 《蘭亭序》 - klikkelj a képre! This copy (摹本) of Lanting Xu 《蘭亭序》 called "Shénlóng běn" copy (神龍本) It is believed that this is a copy by Féng Chéng-sù (馮承素) This copy is kept in the Beijing Palace Museum

According to legend, the original copy was passed down to successive generations in the Wang family in secrecy until the monk Zhi Yong (智永), dying without an heir, left it to the care of a disciple monk, Bian Cai (辯才). Emperor Tai Zong of Tang Dynasty (唐太宗) (599 CE to 649 CE) heard about this masterpiece. He sent messengers on three occasions to retrieve the text, but each time Bian Cai responded that it had been lost. Finally Tai Zong dispatched Xiao Yi (蕭翼) who, disguised as a wandering scholar, gradually gained the confidence of Bian Cai and persuaded him to show him the Preface of the Orchid Pavilion. Thereupon, Xiao Yi seized the work, revealed his identity, and took it back to Tai Zong. Tai Zong loved this masterpiece very much and ordered the top calligraphers such as Yu Shinan (虞世南), Chu Suiliang (褚遂良), Feng Cengsu (馮承素), and Ouyang Xin (歐陽詢) to trace, copy, and engrave into stone for posterity. Tai Zong treasured the work so much that he had the original interred in his tomb, Zhao lin (昭陵), after his death. The authentic Lanting Xu has not been seen since then.

The occasion – Xiu xi (修禊)

Xiu Xi (修禊) was a purification ritual to ward off the evil spirit and bring good fortune. It took place on the third day of the Third Lunar Month. Wang Xizhi (王羲之) composed and wrote this masterpiece on this day of purification ritual in 353 CE (1662 years ago). This ritual is no longer celebrated widely in China today but the event is still commemorated in Shaoxing (紹興), the original place. Scholars still practise it in Lanting every year. Japanese scholars and elites also commemorate the event on that day, in particular in 60th year anniversaries when the lunar year coincides with the year 癸丑 1913, 1973, 2033. In 1973 there was a great exhibition in Japan of everything related to Lanting, and a good catalogue was published.

Translation

永和九年,歲在癸丑,暮春之初,會於會稽山陰之蘭亭,脩稧事也。

In the ninth year of the Yonghe (353 CE), at the beginning of the third moon, on this late spring day we gathered at the Orchid Pavilion in the gui-ji, Shanyin (present-day Shaoxing (紹興) of Zhejiang (浙江) province), for the purification ritual.

羣賢畢至,少長咸集。

All the literati have finally arrived. Young and old ones have come together.

此地有崇山峻領(嶺),茂林脩竹;又有清流激湍,映帶左右,引以為流觴曲水,列坐其次。

Overlooking us are lofty mountains and steep peaks. Around us are dense wood and slender bamboos, as well as limpid swift stream flowing around which reflected the sunlight as it flowed past either side of the pavilion. Taking advantage of this, we sit by the stream drinking from wine cups which float gently on the water.

雖無絲竹管弦之盛,一觴一詠,亦足以暢敘幽情。

Despite of the absence of the grandeur of musical accompaniment, drinking wine and chanting poems give us delight and allow us to exchange our deep feelings.

是日也,天朗氣清,惠風和暢。

As for this day, the sky is bright, the air is fresh and the breeze is mild and bracing.

仰觀宇宙之大,俯察品類之盛。

Looking up, we admire the beauty of the sky and wonder at the immensity of the universe. Looking around us, we see the myriad variety and wonder at their extraordinary diversity.

所以遊目騁懷,足以極視聽之娛,信可樂也。

Stretching our sights and freeing our minds, we can stretch the pleasures of our senses (of sight and sound) to the limit. This is really delighting!

夫人之相與,俯仰一世,或取諸懷抱,悟言一室之內;

People gather together, in a blink, life passes by. Some find relief in freeing their thought and hopes and discuss their ambitions in (the quiet atmosphere of) a study or closet.

或因寄所託,放浪形骸之外。

Some free themselves from the shackles of their body in their search for spiritual refuge.

雖趣(取/趨)舍萬殊,靜躁不同,當其欣於所遇,暫得於己,怏然自足,不知老之將至;

Despite the interests and moods are widely different, tranquillity and recklessness are not the same, we all share one thing: whatever circumstances we meet, we can get some fleeting happiness, and there for just a moment, in self-satisfaction, making us hardly realize how fast we grow old.

及其所之既倦,情隨事遷,感慨係之矣。

When we become tired of our desires and the circumstances changes, disappointment and grief will come.

向之所欣,俛仰之間,已為陳跡,猶不能不以之興懷;

As for all that happiness, in a blink of time, it is already a past tantalizing memory. We cannot help but lament and act in accordance with our emotions.

況脩短隨化,終期於盡。古人云:「死生亦大矣。」豈不痛哉!

Whether life is long or short is up to destiny, but in the end return to nothingness. The ancients said, ‘Birth and death are big events.’ How could it not be agonizing?

每攬(覽)昔人興感之由,若合一契,未嘗不臨文嗟悼,不能喻之於懷。

And look at the cause of sentiment of the ancients, it shows the same origin. We can hardly not mourn before their scripts although our feelings cannot be verbalized.

固知一死生為虛誕,齊彭殤為妄作。

Of one thing I am quite sure: it is foolish to believe that life and death are one, or that long-life can be equated with early death.

後之視今,亦猶今之視昔,悲夫!

The future generations will look upon us just like we look upon the past. How sad!

故列敘時人,錄其所述,雖世殊事異,所以興懷,其致一也。

So we recorded the people here and their works (poems). Even though time and circumstance will change, the cause for their feelings and moods remain the same.

後之攬(覽)者,亦將有感於斯文。

When people look back on us in the future, they will be moved by this prose.

Appreciation of the calligraphy

When Wang wrote the Preface, he was at high spirit after drinking wine with his good friends. There are traces of crossing out and additions. The first 3 lines of this masterpiece show clear regular script strokes. Then brush movement gradually becomes free flowing. The 8th – 11th line (see extract below) forms a beautiful rhythm. From the 12th lines onwards (see extract below) are the best, with the brush movement significantly turns faster in more casual style and takes natural and flowing style of writing, thereby leading to infinite reverie. The entire piece is free and unconstrained with full flavour, demonstrating Wang’s vigorous, robust and flowing running scripts.

It was said that Wang wanted to improve on the writing the next day and copied this work several times. However, he found the original writing was the best.

- The 8th – 11th line forms a beautiful rhythm.

- From the 12th lines onwards the brush movement significantly takes natural and flowing style of writing

Wang’s calligraphy is always fresh and innovative. Each and every stroke of his writing has its own form and postures. Some words appear a number of times in Lanting Xu. The following pictures clearly demonstrate that each word is written differently.

- Of the 324 words in Lanting Xu, the word zhi (之) appears 21 times.

- The words yi 以, suo 所, yi 一, and bu 不 each appears 7 times

- The words yu 於, qi 其, and huai 懷 each appears 5 times.

- The words ye 也, yi 亦, ren 人, and wei 為 each appears 4 times.

- The words zu 足, yang 仰, shi 視, gan 感, xing 興, shi 事, and you 有 each appears 3 times.

- The words ff 夫, da 大, huo 或, shu 殊, shi 世, lie 列, qing 情, wen 文, hui 會, jīn 今, liu 流 and qing 清 each appears 2 times.

- Similarly, the words sui 雖, zhi 知, yi 矣, xin 欣, neng 能, shan 山, you 由, fu 俯, hou 後, zhi 至, and jiang 將 and si sheng 死生 each also appears 2 times.

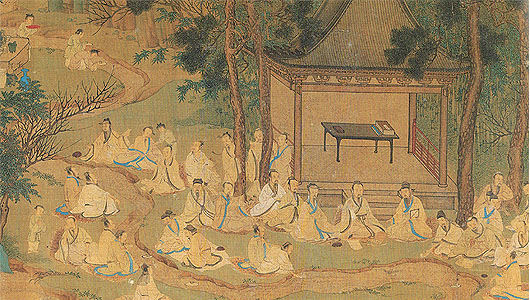

A Painting related to Lanting Xu

A Painting related to Lanting Xu

The above is a painting of the gathering by an anonymous artist in the late Ming Dynasty. It shows guests seated along the banks of a small stream. Servants float wine-cups placed on leaves down the stream. When a cup stopped in front of a person, that person was expected to compose a poem, and if he failed, to drink several cups in forfeit.

Another famous copy of Lantang Xu called Ding Wu Ben 定武本

It is believed that this is a copy version by Ouyang Xun (歐陽詢). It was then engraved onto a piece of polished smooth stone for posterity. From the stone numerous rubbing copies were made. This is one of the rare and finest copies survived. The red seals are the seals of the collectors who once owned this fine copy. This copy is Wu Bing Ben (version) (吳炳本) of Ding Wu Ben and is kept in the Tokyo National Museum. Besides Ding Wu Wu Bing Ben (version) (吳炳本), there are other Ding Wu ben such as Wang Yan Ben (王沇本).

Controversies over the authenticity of Lanting Xu

There has been a great controversy about the authorship of Lanting Xu. Some scholars suggested that it was created two to three hundred years after Wang Xizhi passed away. Li Wentian (李文田), a scholar of the late Qing dynasty and many other people raised these queries. Some scholars even suggested that Zhi Yong (智永) might be the writer of Lanting Xu and he made up the whole story. The reasons for this speculation are :

First, the calligraphy of Wang Xizhi was fresh, elegant and innovative which is very different to the style of his contemporaries at that period. Two in-tomb epitaphs (墓誌銘) of the Eastern Jin were unearthed around 1964 and 1965. One of them was dedicated to Wang Xingzhi (a cousin of Wang Xizhi) and his wife (王興之夫婦墓志) and the other one was an epitaph to Xiè Sāi (謝鰓墓志). The characters of the epitaphs are square (方筆) in the style of Han clerical scripts (漢隸韻味). It was difficult to believe that Wang had abandoned the remnants of this clerical style and attained an elegant and fluidly (流暢) style. Guo Mo-ruo (郭沫若), a well-known modern historian and scholar, has claimed that the discovery of the two epitaphs confirm Li Wen-tian’s speculations.

The counter-argument is that Lanting Xu was written on paper in a relaxed manner and it should be different from the formal writings engraved onto stone to commemorate deceased persons.

Further, in 1909, wooden slips (木簡) and paper scraps (殘紙) of the calligraphy of the Wei (魏) and Jin (晉) Dynasties were unearthed in the lost city of Loulan (樓蘭) in the eastern edge of the Taklamakan Desert (塔克拉瑪幹沙漠) of Xinjiang (新彊). Among those are the letters of Lǐ Bǎi-wén (李柏文書) dated 307 CE, a few decades earlier than the time Lanting Xu was supposed to have been written. The calligraphy was running scripts in an elegant and fluidly (流暢) style. This indicates that running scripts can be common at the time of Jin.

Secondly, in Shi Shuo Xin Yu (世說新語), compiled and edited by Liu Yi-qing (劉義慶) (403 – 444) there is a passage called Lín Hé Xù (臨河序) and the text was identical to the first part of Lanting Xu with the exception of the last part in brown. The words in brown are not in Lanting Xu.

永和九年,歲在癸丑,暮春之初,會於會稽山陰之蘭亭,修禊事也。群賢畢至,少長咸集。此地有崇山峻嶺,茂林修竹,又有清流急湍,映帶左右。引以為流觴曲水,列坐其次。是日也,天朗氣清,惠風和暢,娛目騁懷,信可樂也。雖無絲竹管弦之盛,一觴一詠亦足以暢敘幽情矣。故列敘時人,錄其所述。右將軍司馬太原孫丞公等二十六人,賦詩如左。前餘姚令會稽謝勝等十五人,不能賦詩,罰酒各三鬥。

This passage was shorter and the extra text about philosophical thinking was not present. This led to scholars’ suspicion that Lanting Xu was not authentic because the this extra text could have been faked by people in later years.

Guo Moruo further argued that the sentence 況脩短隨化,終期於盡 (whether life is long or short is up to destiny, but in the end return to nothingness) is a Buddhist way of thinking. Zhi Yong (智永) was a Buddhist monk. Lanting Xu might have been created by him.

The counter-argument is perhaps the shorter version recorded in Shi Shuo Xin Yu is an abridged version of the original Lanting Xu.

No matter who was the writer of Lanting Xu which survived today, it is still revered as the best running calligraphy (天下第一行書). Wang Xizhi is still the Shu Sheng (書聖).