Buddhista kalligráfia, kalligráfia a buddhizmusban

Xiaofeng Cserkész Gábor

index | publikációk | facebook oldalunk

-

书法欣赏.

他们的书法,

佛韵生动,

值得一看。

Scroll down for the English version

Ki tudnád fejezni az érzéseid egyetlen vonásban vagy egyetlen vonással? Meg tudnád mutatni jelenléted egy vonásban? Milyen meditatív folyamatot tükrődik a kalligráfiában? Buddhista vagyok és a kínai kalligráfia művészetét is gyakorlom. Kutatom e két témának történetét - a kalligráfia esztétikáját, technikáit és gyakorlatát a különböző módokon való tanulás feltérképezése révén. A "wu" (無) írásjegye azt jelenti, hogy "nem", "nem" vagy "túl", mely gyakran jelenik meg a Szív Sutrában (心 經) is, amely a Chan buddhizmus egyik legismertebb szövege. Hogyan alakult ez a karakter a Chan központi tanításaként és hogyan került a kalligráfia gyakorlásába? Gyakorlásom közben próbálom ezt megérteni...

Talán nincs még egy olyan ősi civilizáció, amely a kalligráfiát ilyen figyelemre méltó helyzetbe hozta volna, mint a kínai. De olyan vallás sincs még egy, amely oly mélyreható hatással lett volna a régi kínai világra, mint a buddhizmus. Nem meglepő számomra, hogy a buddhista kalligráfia (佛家书法) a kínai művészet egyik csodálatos ága lett. Ha a napi gyakorlatokra gondolok, azt kell mondanom, hogy a kalligráfia gyakorlása igen hatékony eszköznek bizonyul az elmélyülésben, az elcsendesedés buddhista felfogásában. A kínai buddhizmus történetében számos példát láthatsz arra, hogy a buddhista mesterek is nagyon szeretik a kalligráfia művészetét, annak gyakorlását. Ezen a ponton viszont különbséget kell tenni két jelenség / vagy fogalom közt: az egyik a "buddhista kalligráfia", a másik a "buddhisták kalligráfiája".

XingYun Mester (釋星雲法師) munka közben, aki a Fo Guang Shan (佛光山 大乘佛教教團) alapítója. Stílusát úgy nevezik: "one-stroke calligraphy"

A buddhista kalligráfia a buddhista irodalom művészetére utal. A buddhista kalligráfiával foglalkozó művészek nem csak a szerzetesek és hívők (jushi), hanem a világi értelmiségiek is voltak. A buddhisták kalligráfiájának művészete azonban nem feltétlenül tartalmaz szavakat vagy buddhista kifejezéseket: a szerzetesek és mesterek munkái világi szövegekben is megtalálhatóak.

A buddhizmus és a kalligráfia kapcsolata

Számos történelmi feljegyzés található történelmi gyűjteményekben és online könyvtárakban amelyek az indiai (korai) buddhizmus időszakáról szólnak. Hagyomány, hogy nem csak a szerzetesek, hanem a buddhista hívők (jushi) is kötelesek másolni a Szútrák szövegeit. Erre az elfoglaltságra úgy tekintettek, mint az érdemek (福德) felhalmozására, mint a jócselekedetek-, gondolatok eredményes és védő erejére. Az "érdemek" gyűjtése fontos a buddhista gyakorló számára, mert az érdem jó-, kellemes eredményeket hoz, meghatározva, okot szolgáltatva a következő élet minőségéhez és közvetlen módon hozzájárulva az ember fejlődéséhez, megvilágosodásához (正覺). A buddhizmus kínai terjedése jelentősen növelte a kalligráfia fontosságát, közvetlenül járult hozzá annak stílusfejlődéséhez. Az ősi munkák közel fele buddhista tanításokon alapul, melyeket szerzetesek és/vagy buddhista hívők készítettek.

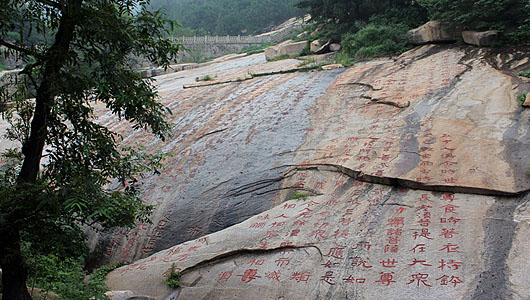

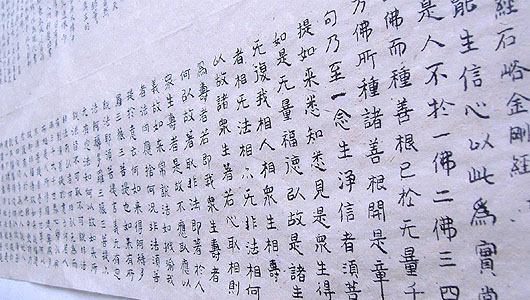

A Szív Szútra vésete előtt (kaishu), mely egy nagy kőtáblán áll a Ziguo Kolostorban (资国寺), Fujian tartományban.

Gondolok itt Zhang Xu (張旭, 675-750) vagy Huai Su (懷素, 737–799) Mesterre a 8. századból. És Xu Yun (虚云和尚, 1840—1959), Yin Guang (印光 1862-1940) Mesterre, aki már egyermekkorában elkezdte a kalligráfia gyakorlását, amirő azt tartotta, hogy különös erőt kölcsönöz számára (“印光大师自小抄写经文,书法有劲力”), Hong Yi’s (弘一大师, 1880–1942) kalligráfiái tiszták, üresek és elegánsak, Qin művészete és festményei kiválóak voltak (“弘一大师书法空灵淡雅,琴诗书画印超凡脱俗”). S ott volt Tai Xu (太虚法师, 1889—1947), “佛人之字,往往予人一種難以言喻之美”) példája is. A buddhista szellemiség a kínai kalligráfia egyik legfontosabb hatásává vált. Különösen a Chan Iskola (禪宗) kapcsolódott szorosan a kínai művészethez, mely hangsúlyozta az empirikus és logika-feletti, intuitív érzéket, amelyre a kínai kalligráfia művészetében is szükség van. A "Kalligráfia Chan -ja" és a "Chan Kalligráfia" [ld.: "a Chan (禪) etimológiája" oldal) fontos elemei a kínai kalligráfia elméletének.

A buddhista kalligráfia formái

Tartalmában és formai különbözőségben a buddhista kalligráfia nagyon gazdag. A régi kínai buddhista kalligráfia kéziratok-, (手稿), feliratok-, (题词) és gravírozások/faragások (文字 记录) formáiban láthatók. A mesterek munkáinak funkcionális besorolása gyakorlati célú munkafolyamatokba soroltak, amelyek ténylegesen gyakorlati célokat szolgáltak, így a kreatív kalligráfia területén érdekes, amelyben a művészek tudatosan megteremtették az esztétikai munkákat motívum indításával. Ha megnézel egy buddhista kalligráfiát, akkor általában azt kai shu (楷書)-, xing shu (行書)-, cao shu (草書) stílusokban láthatod.

Buddhista kéziratok

Az egykori szerzetesek által hátrahagyott kéziratok nem csak magas történelmi értékűek, hanem emellett a művészet területén is kiemelkedő jelentőségűek. Mindenek előtt a Gandhāran buddhista szövegek (犍陀羅 語 佛教 原稿) említésre méltól, melyek a legrégebbi buddhista kéziratok. A korai buddhista irodalom-, a korai buddhista iskolák, valamint a kínai āgama (阿含經, szentírások) irodalom párhuzamos szövegeit jelenti. A kínai kéziratok a Tripitaka -ban (中華 大 藏經 - 漢文 部份) fellelhető kanonikus szövegek új gyűjteménye. E kéziratok leginkább a buddhista szutrák másolásával keletkeztek, mivel a buddhista tanításokat és szútrákat kézzel másolták (így, ahogy ma is gyakorlunk), mielőtt a nyomtatást feltalálták volna. A legtöbb kéziratban van elválasztó vonal, amely segített az egyenletes távolság megtartásában és az azonos vonalon lévő karakterek közötti különbség általában eltérő.

Az egyik kedvenc stílusom a li shu (隶書), amely az északi dinasztiák feliratából és levél-stílusából származik. Ez a pre-Qin időszakban (先秦 時代) indult igazán fejlődésnek az alacsonyrangú tisztviselők által, akik ezt a stílust alkalmaztrák a gyorsabb kormányzati műveletekhez. Ez egyszerűsítette a Zuan Shu bonyolultabb ütemét, a körkörösség helyett inkább egy hajlítást használt. Ezt nevezik Chin Li (秦 隸, Qin dinasztia papi stílusa) vagy Öreg Li -nek (古隸). Különböző írástechnikák, mint a zuoxia (左下, ami "balra lefelé" vagy "Lüe 掠"), a kéziratokban használták, ahol a karakterek élénkek, aktívak, konzervatívak de egyben ünnepélyes formavilágúak. A kortárs kalligráfiai művekhez képest a buddhista kéziratok egyszerűnek, kifinomultnak és elegánsnak tűnnek. A legjellemzőbb rész a keresztirányú vonalak írása amelyet "heng" (橫) -nek nevezünk a kalligráfia művészetében. A mesterek fokozatosan növelték e vonásban az ecset súlyát, így a hengek végén az ecsetet kissé visszahúzva vizuális fókuszpontot hoztak létre. Az ilyen jellegzetességek a "szútra-írás stílusát" (XiejingTi 寫 經 體) hozták létre.

A feliratok művészete

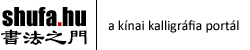

A kéziratok mellett a feliratok is a buddhista kalligráfia egyik fő hordozójává váltak. Amikor Kínában Fujian tartományban voltam 2018 októberében, az egyik buddhista vendéglátónk fafaragó gyárában a templomok és kolostorok nagy buddhista feliratai készülnek. Volt a lehetőségem ezek tanulmányozására, miközben meséltek a híres buddhista templomokról és azok díszeiről. A buddhista barlangok, mint a Yungang (雲岡), a Longmen (龍門) és a Dunhuang (敦煌) a Tang-kor idején alakultak ki, az itt található feliratok pedig nélkülözhetetlenné váltak a későbbi kalligráfusok számára, akik ezeket másolták. Kiváló példa erre a "Longmen Er Shi Pin" (龍門二十品), mely sima, de vad és durva-, nagyszerű stílus, amit mi weibei-nek ismerünk (魏碑, egyébként ez a kai shu alapja is). A barlangok feliratain kívül rengeteg felirat található a templomokban, a hegyekben és a sztúpákban. Példaként említhető a Gyémánt Sūtra felirata a Tai Hegy Szútrakő-völgyében (經石峪).

Tai Hegy Szútrakő-völgye (經石峪)

A Gyémánt Szútra《金剛般若波羅蜜多經》

Fujian, Taimu Shan (太姥山) 《南无阿弥陀佛》

Kalligráfia és buddhista gyakorlat

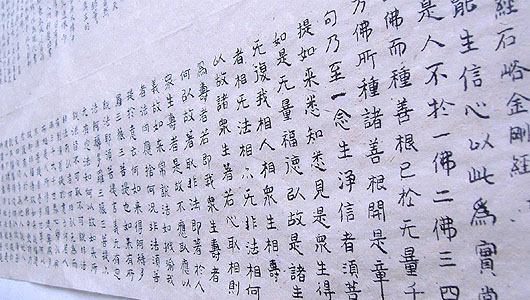

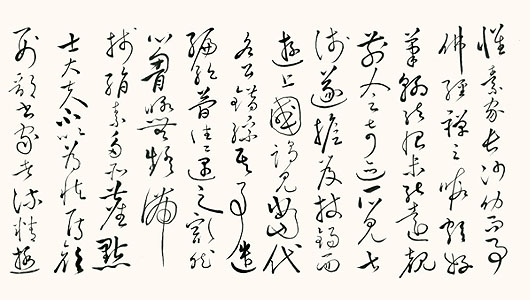

A kalligráfia gyakorlása, az alkotás sok neves szerzetes kedvelt időtöltése volt. A művészek tevékenysége (alkotása) és a buddhista gyakorlat lassan egymásra épült. A buddhista kalligráfia egyik legjelentősebb mestere Huai Su (懷素) volt, aki a kínai történelem egyik legjobb kurzív stílusban (cao shu 草書) megalkotott művét készítette el Huai Su Autobiográfiája (懷素 自叙 帖) címmel 776-ban.

Huai Su Mester Autobiográfiája (懷素 自叙 帖), (776-ból)

Huai Su életéről bár kevés írott emlék maradt fenn (正史), egy korábbi, nem hivatalos dokumentum a tang-korabeli Li Siu (李肇) írt róla a Tang-dinasztia történetének kiegészítésében (唐國史補/卷中):

長沙僧懷素好草書,自言得草聖三昧。棄筆堆積,埋於山下,號曰「筆塚」。

Changsa-béli Huai Su Szerzetes kurzív stílusa jó, önmagáről azt vallotta, hogy alaposan megragadta a "Kurzív stílus samadhi-ját”, valódi lényegét (Zhang Zhi, 張芝, ? -192) a kalligráfia írásjegyében. Elhagytatta és eltemette sok használt ecsetét a hegy lábánál, és ezt a helyet "Az ecsetek sírja” -ként nevezte.

Ebben áll az is, hogy a neves kalligráfus, Huai Su (懷素):

"... nem beszélt Sūtráról (经), nem beszélt Dhyānáról (禅); csak akkor volt vitalitása, amikor a fűírás kalligráfiáját alkotta"

Huang Youwei (黃有維), a Qing-dinasztia idjén élt kalligráfus szerint:

"...azt mondanám: 'A kalligráfia Dharmája olyan, mint Buddhadharma'. A fegyelem kezdete; Javul a meditációban és a bölcsességben; A Szív eredetén valósul meg; A megértés révén válik csodálatossá. Ha elérte a tökéletesség csúcsát, akkor is kimondhatatlan."

Hong Yi Mester (弘一, 1860-1942) volt talán az egyetlen buddhista mester, aki a legnagyobb kalligráfusok közé sorolható. A kínai kalligráfia történetében elsőként ötvözte a buddhista tanításokat a kalligráfiai művészetével, jól mutatva buddhista szemléletet, nem függetlenedve a történelmi tényektől. A kínai kalligráfia értelmezésére is gyakran használt "forma nélküli forma” fogalma-, valamint számos buddhista elmélet is megtalálható a kalligráfia gyakorlása során. Hong Yi kalligráfiája csak a klasszikus és kortárs buddhista szövegek átírására szolgált. Ebben az értelemben munkája példázza a kínai buddhizmus kalligráfiára gyakorolt hatását. Hagyományosan egy kalligráfus utolsó munkáját mesterműnek tekintik alapvetően a technikája és erkölcsi tartalma alapján. Napjainkra azonban ezen utolsó művek közül csak néhány maradt fenn. E szűkösség még értékesebbé teszi ezeket a munkákat. Bei Xin Jiao Ji (悲欣交集) Hong Yi utolsó munkája, amely három nappal a nirvana -ba távozása előtt készült. Azonban a buddhista mesterek és értelmiségiek közötti vélemények különböztek a kalligráfia és a buddhista gyakorlat kapcsolatának tekintetében. Han Yu például úgy véli, hogy a kalligráfia a művészethez tartozik, és a művészetnek a világi életet kell bemutatnia, a világi élet viszont illúzió a buddhizmus tanításában.

Ám a kínai buddhizmus története kalligráfia nélkül és a kínai kalligráfia története a buddhizmus nélkül elképzelhetetlen. Nos, ha a fenti gondolatok felkeltették az érdeklődésed, akkor az alábbi válogatott irodalomban tovább tájékozódhatsz:

- Cai Chongming (蔡崇名), The calligraphic art of the diamond sutra inscribed on the tai mountain 《泰山經石峪金剛經》的書法藝術》.

- Yee Chiang, Chinese calligraphy: an introduction to its aesthetic and technique

- Dai Yiguang (戴一光), 书法文化之旅

- Gong Pengcheng (龔鵬程), A study of the buddhist and dao scripture based on ancient calligraphy (佛道經典書帖考)

- He Jinsong (何勁松) Huang tin-jian’s calligraphic art and its ideological basis of Chan (論黃庭堅書法思想的禪學基礎).

- Hu Jinshan (胡進杉), 法光佛教文化系列演講之六– 佛教與書法

- Wu Youneng (吳有能) The approach of inner subjectivity in the art of chinese calligraphy: with special reference to the Chan (中國書道藝術的內在主體性進路– 以禪宗精神為中心).

- Xiong Bingming (熊秉明) 中国书法理论体系

- Xu Liming (徐利明) 中國書法風格史. 中国书学丛书. 河南美術出版社

Buddhist Calligraphy, Calligraphy in the Buddhism

Xiaofeng Cserkész Gábor

-

书法欣赏.

他们的书法,

佛韵生动,

值得一看。

Can you express your feeling in ONE line? Can you show your presence in ONE line? What kind of meditative process is reflected in calligraphy? I am buddhist and I am a shufa practitioner who research the history of these topics-, aesthetics-, techniques and practice of calligraphy through the exploration of the teachings in a variety of forms as well. The "wu" (無) means "no", "not" or "beyond", which appears in the Heart Sutra (心經), the most widely recited text in Chan Buddhism (禅宗). How this character came to represent a central teaching in Chan and how it has been rendered in the Chinese shufa (中国书法). When I practice, I try to feel it without self...

There isn’t religion that had so profound effects on the old Chinese world like Buddhism, and tere isn’t ancient civilization that puts the calligraphy on a so remarkable position like the Chinese. Not surprise for me that the buddhist calligraphy (佛家书法) presents a magnificent spectacle of Chinese arts and it is what I see, when I'm in China. Thinking about my dayly exercises, my opinion is that the calligraphy has become a very effective method of buddhist practice. It was widely loved by Buddhists - I just follow them - during history of Chinese buddhism until today. And now at this point must make a difference between the two phenomenas: these are the "buddhist calligraphy" and "calligraphy of buddhists".

In Ziguo Monastery (资国寺), Fuding, Fujian. In front of the Heart Sutra, carved by kaishu

The buddhist calligraphy refers to the lettering art that draws subjects from buddhist literature and sutras. The artists involved in buddhist calligraphy art include not only monks and buddhist lay persons (jushi), but also secular intellectuals. The calligraphy of buddhists as art doesn't necessarily present words from Buddhism. The monks and Masters have also created calligraphic works on secular texts.

Relationship between buddhism and calligraphy

There are several historical records in the historical collections and online libraries from Indian Buddhism. Tradition, not only the monks but also the buddhist lay persons (jushi) are required to handwrite copies of sutras. Those deeds were seen as filled with great accumulation of the merits (福德), which is a beneficial and protective force of result of good deeds, acts, or thoughts. The "merit-making" is important to Buddhist practice because the merit brings good and agreeable results, determines the quality of the next life and contributes to a person's growth towards enlightenment (正覺). The Chinese buddhism heightened greatly the importance of calligraphy because the buddhism has contributed tremendously to Chinese calligraphy. Almost half of the famous calligraphic works of ancient China are based on buddhist teachings or created by monks-, buddhist lay persons.

Master XingYun (釋星雲法師) in work. Founder of the Fo Guang Shan (佛光山 大乘佛教教團) monastic order. His style called "tne-stroke calligraphy"

Here, I think about Master Zhang Xu (張旭, 675-750) or Master Huai Su (懷素, 737–799) from the 8th century, and Xu Yun (虚云和尚, 1840—1959), Yin Guang (印光 1862-1940) has started his calligraphy exercises from childhood and the shufa gave excellent power to him. (“印光大师自小抄写经文,书法有劲力”), Hong Yi’s (弘一大师, 1880–1942) calligraphy works are pure, empty and elegant, his poetry of Qin and paintings are excellent. (“弘一大师书法空灵淡雅,琴诗书画印超凡脱俗”), and Tai Xu (太虚法师, 1889—1947), “佛人之字,往往予人一種難以言喻之美”) from the modern age. The buddhist spirituality has become one of the most important influences on Chinese calligraphy. In particular, the Chan School (禪宗) is closely related to the Chinese art. The Chan emphasizes the intuitive and perceptual above the empirical and logical which is exactly what the Chinese calligraphic art needed. The "Chan of Calligraphy" and the "Calligraphy of Chan" [learn more at: "a Chan (禪) etimológiája” page] are important elements in the calligraphic theories.

Forms of buddhist calligraphy

In content and diverse in form the buddhist calligraphy is very rich. The old chinese buddhist calligraphies can be classified into manuscripts (手稿), inscriptions (题词) and engraving scripts (文字记录). The works of buddhist masters can be classified into functional calligraphy which occurred in processes of work for practical purposes, and creative calligraphy in which the artists consciously created aesthetic works, by inditing motif.

Manuscripts in the buddhism

The former monks have left us a rich heritage of manuscripts. These hadn't only high historical value but also high artistic value. I mention first the Gandhāran Buddhist texts (犍陀羅語佛教原稿) are the oldest Buddhist manuscripts yet discovered. The Early Buddhist Literature refers to the parallel texts shared by the Early Buddhist schools as well as the Chinese Āgama (阿含經) - sacred scriptures - literature. The Chinese Manuscripts in the Tripitaka Sinica (中華大藏經–漢文部份) is a new collection of canonical texts. Many of these are created for sutra copying because all buddhist scriptures were copied by hand (as how we practice the calligraphy art today) before printing technique was invented. Most of those manuscripts have separating lines that helped to make even spacing, and the spaces between character on the same line are usually different. If you look at a buddhist scriptures, usually you can see the styles of kai shu (楷書), xing shu (行書), cao shu (草書).

One of my favorite style is li shu (隶書) which is a lettering style from the northern dynasties. This is germinated in the pre-Qin period ( 先秦時代 ), to be used by low-ranking officials for more prompt government operations. It simplified the more complicated strokes of Zuan Shu and used a bend instead of making a roundabout turn. This is called Qin Li (秦隸, clerical style of the Qin Dynasty) or Old Li (古隸). Various writing techniques like zuoxia (左下, which means "towards lower left" or Lüe 掠), youxia (右下 which means "towards lower right" or zhe 磔) were used in those manuscripts where the characters were vivid, active, conservative and solemn. Compared with contemporary secular calligraphic works, the Buddhist manuscripts seem to be simple, unsophisticated and elegant. The most characteristic part is the writing of the transverse lines, this is the "heng" (橫) in the calligraphy art. The masters made the strokes gradually increase in weight. At the end of the hengs, they drew back the tips of brushes emphatically so that the visual focal point stayed there. Characteristics such as these have made the occurrence of the category “Style of Sūtra-Writing” (XiejingTi 寫經體).

Calligraphy as Inscription

In addition to the manuscripts, the inscriptions have become another main carrier of the Buddhist calligraphy. When I was in China, Fujian Province in 2018's October, our one of the buddhist host were kind people who has a wood-carver factory producing the big buddhist inscriptions to the Temples and Monasteries. At there I had chance to see and read up the applyed styles of the buddhist inscription. We discussed about the famous buddhist temples and its adornments more. Regarding the buddhist grottoes, like as Yungang (雲岡), Longmen (龍門) and Dunhuang (敦煌) were constructed during the Tangd period, and the inscriptions formed an indispensable element of those. Many of these inscriptions have been seen as model works by later calligraphers. Outstanding examples are the “Longmen Er Shi Pin” (龍門二十品). They have a plain, wild, hardy and grand style which called weibei (魏碑, as foundation of kai shu). In addition to the inscriptions in grottoes, there have been many inscriptions in temples, mountains and stupas. For instance, the inscription of the Diamond Sūtra 《金剛般若波羅蜜多經》in Tai Mountain Sutra Stone Valley (經石峪) might be understood as a Chinese replica of Indian pilgrim sites associated with the place where the Buddha dried his kasya-robe in the sun after washing it...

Daimond Sutra《金剛般若波羅蜜多經》

Fujian, Taimu Shan (太姥山) 《南无阿弥陀佛》

Shufa and buddhist practice

The Chinese shufa was the hobby and skill of a lot of famous monks. The artist activities and buddhist practice trend to combine each other. One of the first most important buddhist master regarding the buddhist calligraphy art was Huai Su (懷素) Master, and Huai Su's Autobiography (懷素自叙帖) was scribed in 776AD and is considered to be one of the best cursive script - cao shu (草書) works in Chinese history.

Dharma Master Huai Su's Autobiography (懷素自叙帖) in 776.

There are very few, if any, formal official historical notes (正史) on the life of Huai Su. An earlier unofficial documentation on him is Supplement to the history of the Tang dynasty (《唐國史補》) by Tang Dynasty's Li Siu (李肇):

長沙僧懷素,好草書,自言得 「草聖三昧」。棄筆堆積,埋於山下,號曰「筆塚」。

Monk HuaiSu of Changsa adored the cursive script and self-proclaimed he thoroughly grasped the true essence of the "Samadhi of the Cursive Script" (ZhangZhi 張芝, ?-192) in scribing calligraphy. He discarded and buried many of his used brushes at the foot of a mountain and that place was called "The Tomb for the Brushes".

It was said that the famous Buddhist calligrapher Huai Su (懷素):

“didn’t talk about Sūtra, didn’t speak about Dhyāna (禅); he was full of vitality only when he was creating calligraphy of Grass Script”.

In the Song, one of famous calligrapher Huang Tingjian ( 黄庭堅), who was one of the Four Masters of the Song Dynasty (宋四家), and was a younger friend of Master Su Shi and influenced by his and his friends' practice of literati painting (文人画), calligraphy, and poetry, He tried to explain the art with Chan theory:

“There are strokes in the characters as there are ’eyes’ in the sentences of Chan masters. Only those who have the ’eyes’ can know it.”

Huang Youwei (黃有維), a calligrapher of Qing also said:

“I would say: ’The Dharma of calligraphy is like the Dharma of Buddha. It begins with the discipline; It is improved in meditation and wisdom; It is realized in the origin of Heart; It becomes wonderful through comprehension. If it has reached the peak of perfection, it is also unutterable.”

A famous buddhist monk Hong Yi (弘一 1860-1942) was the only buddhist master who can rank among the greatest Chinese calligraphers. In the history of Chinese calligraphy, he is the first monk who combines his buddhist teachings with his calligraphic art. His calligraphic art well serves his religious belief, not independent from the latter as it is in most cases in the history. He uses the Buddhist concept of "a form without form" to interpret Chinese calligraphy, and puts forward a series of buddhist calligraphic theories to guide his practice. Moreover, his calligraphy serves only to transcribe classical and contemporary buddhist texts. In this sense, his calligraphic work exemplifies the influence of Chinese buddhism on Chinese calligraphy. Traditionally the last work of a calligrapher is often considered as his masterpiece according to two standards: its technique and its moral content. Furthermore, few of the last works by great calligraphers have survived. Scarcity makes these works even more valuable. Bei xin jiao ji (悲欣交集) is Hongyi’s last calligraphic work, which was completed three days before his nirvana. However, the opinions differed among Chinese buddhists and intellectuals concerning how to explain the relationship between calligraphy and buddhist practice. For example, Han Yu’s opinion is that, the calligraphy belongs to art, and the art should present earthly life, the earthly life is seen to be illusion in Buddhism.

But, anyway, both the history of Chinese buddhism without calligraphy and the history of Chinese calligraphywithout buddhism are unthinkable. Well, If this article aroused your interest, you can learn more about this topic at:

- Cai Chongming (蔡崇名), The calligraphic art of the diamond sutra inscribed on the tai mountain 《泰山經石峪金剛經》的書法藝術》.

- Yee Chiang, Chinese calligraphy: an introduction to its aesthetic and technique

- Dai Yiguang (戴一光), 书法文化之旅

- Gong Pengcheng (龔鵬程), A study of the buddhist and dao scripture based on ancient calligraphy (佛道經典書帖考)

- He Jinsong (何勁松) Huang tin-jian’s calligraphic art and its ideological basis of Chan (論黃庭堅書法思想的禪學基礎).

- Hu Jinshan (胡進杉), 法光佛教文化系列演講之六– 佛教與書法

- Wu Youneng (吳有能) The approach of inner subjectivity in the art of chinese calligraphy: with special reference to the Chan (中國書道藝術的內在主體性進路– 以禪宗精神為中心).

- Xiong Bingming (熊秉明) 中国书法理论体系

- Xu Liming (徐利明) 中國書法風格史. 中国书学丛书. 河南美術出版社